Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) was a German organist and composer whose work is today regarded as amongst the finest of mature baroque music (c. 1600-1750).

More famous as an organist than as a composer in his own lifetime, Bach’s rich legacy encompasses sacred and secular works, notably cantatas, organ pieces, and concertos which influenced many later composers.

More famous as an organist than as a composer in his own lifetime, Bach’s rich legacy encompasses sacred and secular works, notably cantatas, organ pieces, and concertos which influenced many later composers.

Amongst Bach’s most critically acclaimed music are his Magnificat, his Mass in B minor, and the Brandenburg Concertos. The famous melody ‘Air on the G String’, which uses the lowest string on the violin, is taken from Bach’s third orchestral suite.

Early Life

Johann Sebastian Bach was born on 21 March 1685 in Eisenach in Thuringia, central Germany. The house where it is thought he lived as a child is in the Rittergasse, today a museum dedicated to the composer.

Johann Sebastian came from a long line of musicians, several of them important in the region as choirmasters, church organists, and court entertainers. His father, Johann Ambrosius Bach (1645-1695), was a musician for the local council of Eisenach.

Johann Sebastian’s mother was Maria Elisabetha, and he had seven siblings.

Johann Sebastian was left an orphan when his mother died in May 1694 and then his father shortly after in the autumn of the same year. Still only ten years old, Johann Sebastian was taken into the care of his eldest brother Johann Christoph Bach.

This brother was another organist, this time in St Michael’s Church in Ohrdruf. When he was 15, Johann Sebastian went to distant Lüneburg to study at St. Michael’s school there.

His musical education continued when his excellent treble voice made him a valuable member of the school’s choir.

Bach was a keen listener of others, and he visited Hamburg more than once in order the hear the noted organist Johann Adam Reincken (1623-1722) play in the city’s St. Catherine’s Church, a walk of some 48 km (30 mi).

Organist at Arnstadt

Leaving school in 1702 and returning to Thuringia, Bach pursued a musical career with varying degrees of success, managing to earn a wage by playing the violin in the Weimar ducal court orchestra.

His fortunes rose considerably when he was called in to test the new organ of the New Church in Arnstadt. As a result of a public recital, which went down well with the congregation, he was appointed the church’s official organist in August 1703, which meant that he was charged with maintaining the instrument and accompanying church services.

Bach was not always easy to work with, as the historian of music W. Thompson notes: “he had a stubborn and at times arrogant streak, which caused problems with all his employers”.

Bach once drew his dagger in an argument with a local youth who had resented Bach disparagingly calling him a bassoonist incapable of creating sounds more pleasant than the bleat of a goat.

In 1705, Bach went missing for four months when he had only been granted four weeks study leave. Bach had spent the time listening to the celebrated organist Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) in Lübeck.

Even when fulfilling his obligations, Bach’s musical genius and experimentation with standard forms were not quite appreciated by his employers or the conservative congregations that listened to his music.

In 1706, Bach got into more hot water when he was accused of permitting a lady into the organ loft.

A clash of personalities, Bach’s unconventional behaviour, his stubbornness, sometimes short temper, and the musician’s experimentation with new organ music may all explain why he moved on to Mühlhausen in June 1707.

Here he was once again appointed the council’s organist, and in October of the same year, he married his second cousin Maria Barbara Bach.

Maria may have been the lady who had seen more than she should have in the organ loft, but the evidence is inconclusive.

The couple would go on to have six children, the first of which, Catharina Dorothea, was born on 29 December 1708.

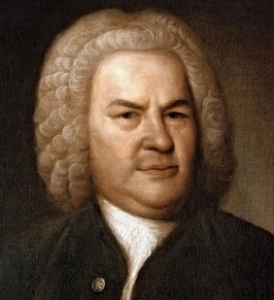

The historian H. C. Schonberg gives the following physical description of Bach based on numerous available contemporary portraits:

A rather massive head, a strong physique…the prominent nose, the fleshy cheeks, the outthrust chin, the severe lips. It is a tough, strong masculine face, the face of a man who will stand up for his rights. It is an uncompromising face: not the look of a fanatic, but certainly with the look of one who is determined to have his own way.

The Weimar Court

Despite his good salary, Bach was soon frustrated at the limitations put on sacred musical performances by the church elders at Mühlhausen.

From June 1708 to 1717, Bach was back working at the Weimar court, appointed by Duke Wilhelm Ernst to be the organist for the castle’s chapel, the Kapellmeister, and to provide chamber music when required.

From June 1708 to 1717, Bach was back working at the Weimar court, appointed by Duke Wilhelm Ernst to be the organist for the castle’s chapel, the Kapellmeister, and to provide chamber music when required.

It is this period that Bach’s first original compositions date to. In 1714, he was promoted to Konzertmeister (director of the court orchestra), a position that required a new cantata each month.

A cantata is a dramatic work performed in Sunday church services, which involves both singers and instruments.

Bach was aware of developments in French and Italian music of the period, and he often innovated, notably with the cantata form, reducing the prominence of the chorus and including in his works more quasi-operatic elements.

Another trademark characteristic of Bach’s cantatas is “his delight in finding an exact musical equivalent to the imagery of the verse”.

Prince Leopold

By 1717, Bach and Duke Wilhelm had fallen out. The duke had strictly forbidden any of his employees to work at the rival court of the co-regent Duke Ernst August, but Bach had ignored this, even performing a birthday cantata dedicated to the duke.

The composer announced his intention to move on to the court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. Leopold certainly appreciated Bach’s talent, offering him a handsome cash bonus upfront for moving court and promising a generous salary thereafter.

Duke Wilhelm did not want to lose Bach’s talents, though, and he kept his organist a prisoner for four weeks. When the situation became impossible, Bach took up his new appointment as Prince Leopold’s chief musician from New Year’s Day 1718.

Prince Leopold was a Calvinist, and so Bach now composed more secular music, including his celebrated six concertos that collectively became known as the Brandenburg Concertos (they were dedicated to Margrave Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg).

Bach diversified his works beyond the organ and cantatas. Now the composer created works for soloists of other instruments like the harpsichord, violin, flute, and cello.

The court possessed a collegium musicum, a permanent in-house orchestra of talented musicians, and Bach, as its head, composed pieces for the musicians to practise together and as soloists; he also composed pieces designed to teach his children and various other students in his care.

There were occasional guest virtuoso soloists to work with, and Bach was given funds to buy new instruments for his team.

This may have been Bach’s happiest professional period as he “was extremely prolific at this time, composing in virtually every genre of chamber music, and in a wide variety of styles”.

Bach’s work was in demand, he even wrote, according to legend, the Goldberg Variations (1722) for an aristocrat suffering from insomnia.

Personal tragedy struck in July 1720 when Maria Barbara died while the composer had been in Karlovy Vary (then known as Carlsbad) in Bohemia with his employer.

Bach could not return home in time for his wife’s burial. In another blow, the composer’s elder brother and father figure Johann Christoph died the next February.

Move to Leipzig

Bach married for a second time in December 1721, his wife was the court singer Anna Magdalena Wilcken (1701-1760), with whom he had 13 children.

In May 1723, Bach was appointed the choirmaster, organist and teacher of the Thomaskirche (Saint Thomas’ Church) in Leipzig. Here Bach composed works to be performed in the city’s four main churches and taught music.

His relationship with the town council, as it seems to have been everywhere, was difficult. The composer was not at all pleased with the quality of the 54 members of his choir, describing them as “17 usable, 20 not yet usable, and 17 wholly unsuitable”.

A perfectionist, Bach was probably able to play all of the instruments in his orchestra (he very likely tuned them all personally prior to a public performance), and he could detect even the slightest of errors during a performance.

The composer was certainly not slow to point out any imperfections in the technique of his musicians.

Bach composed a prolific amount of works in this period, almost a cantata each Sunday.

In 1729, Bach composed the funeral cantata for his old employer Prince Leopold. Aware of his talents – further evidence of which included the publication of many of his works in print – he was dissatisfied with his salary, and Bach was always rather particular about money, as his personal letters indicate.

Bach continued to lament the lack of talent of his orchestra, with keyboard soloists, especially, finding it difficult to perform well Bach’s complex pieces which required both nimble fingers and intricate footwork for the pedals. The audience was often left a little bemused, too, by the more elaborate works like St. Matthew Passion.

The composer’s fame, at least in musical circles, was confirmed in 1736 with continued demand for his organ recitals and his appointment as the Royal Court Composer to the King of Saxony.

Another career high point was a visit to Berlin in 1747 and an audience with Frederick the Great, King of Prussia (l. 1712-1786). The king’s working of a fugue subject was transformed by Bach into his The Musical Offering (a fugue being a composition where successive parts, vocal or instrument, imitate each other based on a common theme)

Bach was a Lutheran Protestant in an area particularly known for this branch of the Christian faith. Indeed, Martin Luther had spent time imprisoned in the imposing Wartburg Castle in Bach’s hometown of Eisenach and even attended the same school that Bach had done.

It should come as no surprise then that Bach’s music often focussed on religious themes, especially the cantatas.

Bach was influenced by earlier composers, particularly the concertos and organ works of Buxtehude, Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706), and the more versatile Italian musical style of Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) and Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741).

Bach was also a product of his time. He composed music in a period where musical works are loosely categorized into what we today call baroque music, that is many varieties of music but with a collective identity of “mysticism, exuberance, complexity, decoration, allegory, distortion, the exploitation of the supernatural or grandiose…movement, disturbance, doubt”.

Bach’s major works were (with first performance dates):

222 sacred and secular cantatas

7 harpsichord concertos

4 orchestral suites

3 violin concertos

Brandenburg Concertos (1721)

Goldberg Variations (1722)

Magnificat in E Flat (1723)

Saint John Passion (1724)

Saint Matthew Passion (1729)

Christmas Oratorio (1734)

Italian Concerto (1735)

The Musical Offering (1747)

Mass in B Minor (1749)

In addition to the above and other works, Bach compiled a two-volume collection of 48 preludes and fugues covering all the major and minor keys known as The Well-Tempered Clavier (1722-42).

At the time, ‘clavier’ referred to a variety of keyboard instruments and not exclusively to the then-dominant harpsichord.

The Art of Fugue (1750), a monumental series of contrapuntal (two lines played simultaneously) variations was left unfinished.

Both of these important and influential works may have been compiled as a sort of practice for accomplished keyboard players or as a record of Bach’s own studies and variations.

Bach’s last work in The Art of Fugue is a complex triple fugue which ends abruptly with notes spelling out his name (remembering that in German nomenclature B is B flat and H is B-natural).

Death & Legacy

In his last years, Bach was almost totally blind and rather impoverished, his baroque music now seen as dated as tastes had moved on.

Bach died of a stroke in Leipzig on 28 July 1750. He was interred inside St. John’s Church (originally near the south door but later moved to near the altar).

Two of Bach’s sons with Maria Barbara, Wilhelm Friedemann (1710-1784) and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788), and one son with Anna Magdalena, Johann Christian (1735-1782) also became noted composers, continuing the long family tradition.

Contrary to popular tradition, Bach’s work was never really forgotten within the music world, but his reputation as one of the greatest of all composers soared in the 19th century when fellow German composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) discovered many of his choral works (diligently kept by Bach’s musical descendants).

Mendelssohn conducted a performance of St. Matthew Passion in Berlin in 1829. Once again, the public could hear the music of Bach, and it was so appreciated by audiences that his works continued thereafter to be publicly performed.

Bach was a favourite composer of many other musicians who followed.

Both Robert Schumann (1810-1856) and Franz Liszt (1811-1886) composed fugues that resembled Bach’s own style. Schumann insisted on playing at least one Bach piece every day.

Franz Schubert (1797-1828) said that “Johann Sebastian Bach has done everything completely, he was a man through and through”. Other admirers included Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) and Arthur Honegger (1892-1955).

Today, Bach enjoys a position as one of the greatest of all classical composers and, along with George Frideric Handel, he is regarded as the greatest exponent of baroque music.

As Schonberg notes, “where most composers of his day would confine themselves to the rules, Bach made the rules”. Johann Sebastian Bach’s music continues to achieve its composer’s ambition, for Bach himself “once said that it was his purpose to dispel sadness and bring joy”.

Reference: https://www.worldhistory.org/Johann_Sebastian_Bach/

–

Brandenburg Concerto No. 1

In the video, Claudio Abbado and the Orchestra Mozart perform Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046 at the Teatro Municipale Valli in Reggio Emilia, Italy.

00:00 I. Allegro

03:49 II. Adagio

06:55 III. Allegro

10:48 IV. Menuet – Trio – Menuet – Polonaise – Menuet – Trio – Menuet

–

Brandenburg Concerto No. 2

In the video, Claudio Abbado and the Orchestra Mozart perform Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 at the Teatro Municipale Valli in Reggio Emilia, Italy.

Of the six Brandenburg Concertos, this is likely the most well-known – with its wonderfully ceremonial, blaring trumpet in the first and third movements. In Bach’s day, the trumpet was generally reserved solely for military music. This makes the use of trumpet in this second Brandenburg Concerto an anomaly, shaping the direction of the piece in striking fashion. Unusual in and of itself is the combination of the four solo instruments; alto recorder, violin, oboe, and trumpet – which compete in a virtuosic fugue in the outer movements.

The most beautiful moment of this concert recording comes as a surprise, at its close. During the applause – which itself lasts more than two minutes – the stage is being showered with flowers. Euphorically, the musicians strike up an encore, repeating the last movement – the Allegro assai of the Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 – this time faster and with more intensity. The sopranino recorder plays the part of the alto recorder, and the last trumpet note of the stunning piece is played an octave higher – the triumphant finale to a magnificent concert.

Giuliano Carmignola – Violin

Reinhold Friedrich – Trumpet

Lucas Macías Navarro – Oboe

Michala Petri – Recorder

00:00 I. Allegro

04:45 II. Andante

08:30 III. Allegro assai

11:11 Applause

13:25 Encore: III. Allegro assai

–

Brandenburg Concerto No. 3

In the video, Claudio Abbado and the Orchestra Mozart perform Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048, at the Teatro Municipale Valli in Reggio Emilia, Italy (2007).

00:00 I. Allegro

05:19 II. Adagio ma non tanto

05:44 III. Allegro

–

Brandenburg Concerto No. 4

In the video, Claudio Abbado and the Orchestra Mozart perform Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049, at the Teatro Municipale Valli in Reggio Emilia, Italy (2007).

00:00 I. Allegro

07:11 II. Andante

10:54 III. Presto

–

Brandenburg Concerto No. 5

In the video, Claudio Abbado and the Orchestra Mozart perform Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050, at the Teatro Municipale Valli in Reggio Emilia, Italy (2007).

00:00 I. Allegro

09:00 II. Affettuoso

14:03 III. Allegro

–

Brandenburg Concerto No. 6

In the video, Claudio Abbado and the Orchestra Mozart performs Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B-flat major, BWV 1051, at the Teatro Municipale Valli in Reggio Emilia, Italy (2007).

00:00 I. Allegro

06:00 II. Adagio ma non tanto

10:47 III. Allegro

–

Goldberg Variations, BMV 998

In this video Glenn Gould plays the Goldberg Variations. The original recording was made in June 1955. The present version is remastered from the original recording.

-Aria 0:00

-Variation 1 1:56

-Variation 2 2:41

-Variation 3 (Canon at the unision) 3:19

-Variation 4 (Passepied?) 4:15

-Variation 5 4:45

-Variation 6 (Canan at the second) 5:23

-Variation 7 (Al tempo di Giga) 5:58

-Variation 8 7:07

-Variation 9 (Canon at the third) 7:53

-Variation 10 (Fughetta) 8:32

-Variation 11 9:15

-Variation 12 (Canon at the fourth [in inversion]) 10:10

-Variation 13 (Sarabande) 11:07

-Variation 14 13:21

-Variation 15 (Canon at the fifth [in inversion, G minor]) 14:20

-Variation 16 ([French] Overture) 16:40

-Variation 17 17:59

-Variation 18 (Canon at the sixth) 18:53

-Variation 19 (Minuet?) 19:40

-Variation 20 20:23

-Variation 21 (Canon at the seventh [G minor lament bass]) 21:11

-Variation 22 (alla breve, stile antico) 22:56

-Variation 23 23:39

-Variation 24 (Canon at the octave) 24:34

-Variation 25 (Adagio [Aria in G minor]) 25:32

-Variation 26 32:07

-Variation 27 (Canon at the ninth) 33:00

-Variation 28 (Trilled toccata) 33:51

-Variation 29 35:03

-Variation 30 (Quodlibet) 36:04

-Aria 36:53

–

Toccata and Fugue in D minor BWV 565

In this video the Toccata and Fugue is performed by organist Hans-André Stamm on the Trost Organ of the Stadtkirche in Waltershausen, Germany.

In this video Xaver Varnus plays the Toccata and Fugue (edited by Mendelssohn) on the great Sauer Organ of the Berliner Dom. It was recorded live on the Opening Night of the “Berliner Internationaler Orgelsommer 2013”.

–