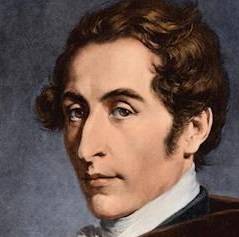

Carl Maria von Weber

Carl Maria von Weber (born Nov. 18, 1786, Eutin, Holstein, Germany — died June 5, 1826, London, Eng.) was a German composer and opera director during the transition from Classical to Romantic music, noted especially for his operas Der Freischütz (1821; The Freeshooter, or, more colloquially, The Magic Marksman), Euryanthe (1823), and Oberon (1826).

Der Freischütz, the most widely popular German opera that had been written to date, established German Romantic opera.

Weber was born into a musical and theatrical family.

His father, Franz Anton, who seems to have wished upon the family the baronial von to which it had in fact no title, was a musician and soldier of fortune who had formed a small traveling theatre company.

His mother, Genovefa, was a singer; his uncles, aunts, and brothers were to some degree involved in music and the stage.

His mother, Genovefa, was a singer; his uncles, aunts, and brothers were to some degree involved in music and the stage.

Carl Maria was a sickly child, having been born with a diseased hip that caused him to limp throughout his life.

When he began to show signs of musical talent, his ambitious father set him to work under various teachers in towns visited by the family troupe in the hope that he might prove a Mozartean prodigy.

Among these instructors was Michael Haydn, the younger brother of the composer Joseph Haydn.

Under Haydn, Weber wrote and published his Opus 1, Sechs Fughetten (1798).

The troupe paused briefly in Munich, where Weber learned the art of lithography under its inventor, Aloys Senefelder.

Moving on to Freiberg, the Webers planned to set up a lithographic work in order to propagate the young composer’s music.

The scheme fell through; but meanwhile, Weber had composed his first opera, Das Waldmädchen (“The Forest Maiden”), which partially survives. Staged at Freiberg in 1800, it was a failure.

The scheme fell through; but meanwhile, Weber had composed his first opera, Das Waldmädchen (“The Forest Maiden”), which partially survives. Staged at Freiberg in 1800, it was a failure.

On a return visit to Salzburg, Weber completed his first wholly surviving opera, Peter Schmoll und seine Nachbarn, which also failed when it was produced in Augsburg in 1803.

Weber resumed his studies under the influential Abbé Vogler, through whom he was appointed musical director at Breslau (now Wrocław, Pol.) in 1804.

After many difficulties, occasioned by the inexperience of a young director in putting through reforms, and a near-fatal accident in which he permanently impaired his voice when he swallowed some engraving acid, Weber was forced to resign.

He was rescued by an appointment as director of music to Duke Eugen of Württemberg, for whose private orchestra he wrote two symphonies.

They are attractive, inventive works, but the symphony, with its dependence on established forms, was not the natural medium of a composer who sought to bring Romantic music to a freer form derived from literary, poetic, and pictorial ideas.

They are attractive, inventive works, but the symphony, with its dependence on established forms, was not the natural medium of a composer who sought to bring Romantic music to a freer form derived from literary, poetic, and pictorial ideas.

Next Weber was a secretary in the court of King Frederick I of Württemberg.

Here he lived so carelessly and ran up so many debts that, after a brief imprisonment, he was banished.

The principal fruits of these years (1807–10) were his Romantic opera Silvana (1810), songs, and piano pieces.

Weber and his father fled to Mannheim, where he was, in his own words, “born for the second time.”

He made friends with an influential circle of artists, from whom he stood out as a talented pianist and guitarist; he was also remarkable for his theories on the Romantic movement.

Moving on to Darmstadt, he met Vogler again, as well as the German opera composer Giacomo Meyerbeer.

From this period came principally the Grand Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Opus 11, for piano, and the delightful one-act opera Abu Hassan (1811).

Disappointed in not winning a post in Darmstadt, Weber traveled on to Munich, where his friendship with the clarinet virtuoso Heinrich Bärmann led to the writing of the Concertino, Opus 26, and two brilliant, inventive clarinet concerti.

Disappointed in not winning a post in Darmstadt, Weber traveled on to Munich, where his friendship with the clarinet virtuoso Heinrich Bärmann led to the writing of the Concertino, Opus 26, and two brilliant, inventive clarinet concerti.

In all, he was to write six clarinet works for Bärmann, with whom he also toured.

The clarinet remained, with the horn, one of the favorite instruments of a composer whose ear for new sounds and new combinations of instruments was to make him one of the greatest orchestrators in the history of music.

Weber was also one of music’s great piano virtuosos; his own music reflects something of the brilliance and melancholy and exhibitionist charm described by his contemporaries when he performed it.

From 1809 to 1818 Weber also wrote a considerable number of reviews, poems, and uncompromising, stringent music criticisms.

All his work, music, and critical writings furthered the ideals of Romanticism as an art in which feeling took precedence over form and heart over head.

Appointed conductor of the opera at Prague in 1813, after a period in Berlin during which he caught the patriotic fervor of the day in some stirring choruses and songs, Weber was at last able to put his theories into full practice.

His choice of works showed his care for Romantic ideals, and his choice of artists showed his concern for a balanced ensemble, rather than a group of virtuosos.

Furthermore, by publishing introductory articles to his performances, he saw to it that his audiences were carefully prepared.

Obstacles again appeared: a stormy love affair left him disconsolate, and opposition to his reforms forced him to resign in 1816.

His reputation by now, however, was such that he was able to secure an appointment as director of the German opera at Dresden, beginning in 1817.

The same year he married one of his former singers, Caroline Brandt.

Dresden was a city more backward than most in Germany, and it had a flourishing rival Italian opera.

As the prophet of a German national opera, Weber was faced with even greater difficulties.

Happily married, he applied himself energetically to his work, assuming full control over all aspects of the operatic production.

No detail escaped him: he supervised repertory, recruitment, casting, scenery, lighting, and production, as well as the orchestra and the singers, taking care to see that every performer fully understood the words and plot of each opera.

These tasks left him little time for writing operas himself, however, especially in view of the inexorable advance of his tuberculosis.

He nevertheless produced several works during this period, including the last of his four piano sonatas, many songs, and shorter piano solos, such as the famous Invitation to the Dance (1819), and the Konzertstück, Opus 79 (1821), for piano and orchestra.

It was also in Dresden that Weber began to work on Der Freischütz, which was an immediate success when it was performed in Berlin in 1821.

The story, deriving from folklore, concerns a man who has sold his soul to the Devil for some magic bullets that will enable him to win a marksmanship contest and with it the hand of the lady he loves.

The opera presented, for the first time, things familiar to every German: the simple village life, with its rough humor and sentimental affections, and the surrounding forest, with its smiling appearance concealing supernatural horror.

Above all, the characters, from the cheerful huntsmen and village girls to the simple, valiant hero and the prince who rules over them, were all—with the tuneful, sensational music—a mirror in which every German could find his reflection.

In Der Freischütz Weber not only helped liberate German opera from French and Italian influences but, in his novel orchestrations and in his choice of a subject matter containing strong supernatural elements, he laid the foundations of one of the principal forms of 19th-century opera.

Der Freischütz made Weber a national hero.

His next opera, Euryanthe was a more ambitious work and a larger achievement, anticipating Wagner as his piano music does Chopin and Liszt.

It nevertheless foundered on its clumsy, though not intolerable, libretto.

When Covent Garden in London commissioned a new opera, Weber took on the task of learning English and working with a librettist, James Robinson Planché, by correspondence.

His motive was to earn enough money to support his family after his death, which he knew to be not far off.

In form, Oberon was little to his taste, having too many spoken scenes and elaborate stage devices for a composer who had always worked for the unification of the theatrical arts in opera.

But into it, he poured some of his most exquisite music, and he traveled to London for the premiere in 1826.

Barely able to walk, he was sustained by the kindness of his host, Sir George Smart, and by the longing to get home again to his family.

Oberon was a success and Weber was feted, but his health was declining fast.

Shortly before he was due to start the journey back to Germany, he was found dead in his room.

–

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73

Weber wrote this for the clarinettist Heinrich Bärmann in 1811. The piece is highly regarded in the instrument’s repertoire. It is written for clarinet in B♭.

The work consists of three movements:

Allegro (0:15)

Adagio ma non troppo (8:32)

Rondo. Allegretto (15:25)

In the video the concerto is performed by Juan Ferrer with the Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia conducted by Jesús López Cobos.

Here is another video performance by the legendary clarinetist Karl Leister with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Rafael Kubelik.

–

Clarinet Concerto No. 2 in E♭ major, Op. 74

This was written in 1811, and premiered on December 25, 1813. It was dedicated to Heinrich Baermann, who also was the soloist at the premiere.

The movements are:

1. Allegro

2. Romanze. Andante con moto

3. Alla Polacca

The video presents a live performance of the concerto by Kevin Spagnolo with the Brussel Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Antonio Saiote.

In this video, the concerto is performed by Walter Boeykens with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by James Conlon.

This video presents a performance of the concerto by the legendary clarinetist Ernst Ottensamer with the Wiener Philharmoniker conducted by Sir Colin Davis.

–

Concertino for Clarinet in E-flat major, Op. 26

This was also written for clarinetist Heinrich Bärmann in 1811. Weber wrote the work in three days between March 29 and April 3. Bärmann learned the work over the next three days and the command performance, for which King Maximilian I of Bavaria purchased 50 tickets, took place on the evening of April 5.

The concertino unfolds in one movement. The form is theme and variations.

In the video the concerto is performed by Joan Enric Lluna with the Real Filarmonia de Galicia.

–

Clarinet Quintet in B♭ Major, Op. 34

This was composed from 1811 to 1815. It is essentially a clarinet concerto with string quartet accompaniment being full of virtuosic technical passages and coloratura vocal passages for the soloist.

It has four movements:

Allegro

Fantasia

Menuetto, capriccio presto

Rondo, allegro giocoso

In the video the quintet is performed live by Alessandro Carbonare with I Solisti Aquilani.

–

Konzertstück in F minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 79

This was started in 1815 and was only completed on the morning of the premiere of his opera Der Freischütz, 18 June 1821. He premiered it a week later, on 25 June, at his farewell Berlin concert.

The video presents a performance by Alexei Volodin with the SWR Symphonieorchester conducted by Dima Slobodeniouk.

–

Piano Concerto No.1 in C-major, Op.11

Weber composed this in 1810 and gave the work its premiere in Mannheim the same year. Stylistically, the work’s overall structure is clearly based on the model of Mozart’s concertos, and many of the work’s details are drawn from Beethoven’s own Piano Concerto in C major.

The movements are:

Mov.I: Allegro 00:00

Mov.II: Adagio 08:54

Mov.III: Finale, presto 13:17

In the video, the concerto is performed by Peter Rösel with the Staatskapelle Dresden conducted by Herbert Blomstedt.

–

Piano Concerto 2 in E Flat Major Op. 32

According to his diary, Weber bought a copy of Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ in early 1811.

His response was to write a concerto not just in the same key, but complete with a partially muted string Adagio in B major and a rumbustiously galloping closing rondo in 6/8.

The E flat Concerto is both Weber’s ‘Emperor’ and an eloquent Beethoven homage. It was a favorite ‘visiting card’ of Weber. He played it often, always to popular acclaim.

The movements are:

I. Allegro maestoso

II. Adagio

III. Rondo: Presto

In the video, the concerto is performed by Benjamin Frith with the RTE Sinfonietta conducted by Proinnsias O Duinn.

–

Rondo Brillante, Op.62

This is an excellent example of what has been called Weber’s ‘glass chandelier style’, the Rondo Brillante’s crystalline brilliance exploits the piano’s upper treble range (and the pianist’s right hand) to great effect. This is a true showpiece.

The video shows a performance by Kristina Moditch.

–

Der Freischütz

Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz overture is a typical product of the Teutonic romantic movement of the early nineteenth century.

Weber was the direct forerunner of Wagner. The dramatic tension engendered by tremolando strings and heavy drum notes, which one finds in the introduction of this overture, became almost a bad habit with Wagner in tragic situations.

Ouverture

The video shows a performance by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Ondřej Vrabec. The recording took place in the Dvořák Hall, Rudolfinum, Prague in 2015.

Agathe – Wie nahte mir der Schlummer – Aria

In this older video, the aria is performed by the legendary soprano Gundula Janowitz with the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Alain Lombard.

Gundula Janowitz sings with a beautiful golden tone and precise technique without scooping to high notes or heavy vibrato. Some European conductors stated that Gundula Janowitz was their “soprano of choice.” An opera director told, “There has been no one like her since.”

Oberon Overture

Oberon, the final opera of Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826), was premiered at London’s Covent Garden in 1826. The three-act opera, set in English with spoken dialogue, was described as “one of the most remarkable combinations of fantasy and technical skill in modern music.”

Born five years before the death of Mozart, Carl Maria von Weber was a contemporary of Beethoven and Schubert.

In his music, we hear the full Romantic orchestra spring to life.

As music director in the opera houses of Prague and Dresden, Weber was influential in expanding the size of the orchestra. Perhaps as a result, he was one of the first conductors to use a baton.

In Weber’s orchestral music, the distinct personas of the instruments take on new significance. Debussy observed that the sound of Weber’s orchestra was “obtained through the scrutiny of the soul of each instrument.”

Drawing on music from the opera, the Overture to Oberon unleashes an exuberant conversation between instrumental voices.

In the video, the overture is performed in the Royal Opera House Covent Garden 01-12-1999. The conductor is the legendary Bernard Haitink.

In this video, the overture is performed live by the FVG Mitteleuropa Orchestra conducted by Giovanni Pacor.

Symphony No. 1 In C Major, Op. 19

This symphony was written in 1806–1807 for Duke Eugen of Württemberg, who employed Weber from 1806. The symphony has a prominent part for the oboe, the instrument the Duke liked to play.

It has four movements:

Allegro con fuoco

Andante

Scherzo. Presto

Finale. Presto

In the video, the symphony is performed by the London Classical Players conducted by Roger Norrington.

Symphony No. 2 In C Major

This was written in a week’s time in January of 1807, and like the first symphony, it has a prominent part for the oboe.

The movements are:

I. Allegro : 00:00

II. Adagio ma non troppo : 07:44

III. Menuetto – Trio : 12:32

IV. Finale : Scherzo presto : 14:30

In the video, the symphony is performed by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Wolfgang Sawallisch.

Aufforderung zum Tanze (Invitation to the Dance) Op. 65

Originally this is a piano piece in rondo form from 1819. Weber dedicated it to his wife Caroline (they had been married only a few months).

In 1841 Hector Berlioz made an orchestration of the work.

In the video, the orchestration of this popular piece is performed by the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Perry So.

–