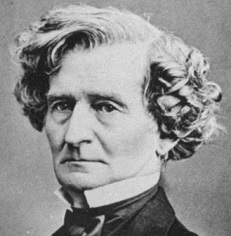

Hector Berlioz

Louis-Hector Berlioz (11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869) was a French Romantic composer and conductor. His output includes orchestral works such as the Symphonie fantastique and Harold in Italy, choral pieces including the Requiem and L’Enfance du Christ, his three operas Benvenuto Cellini, Les Troyens and Béatrice et Bénédict, and works of hybrid genres such as the “dramatic symphony” Roméo et Juliette and the “dramatic legend” La Damnation de Faust.

The elder son of a provincial doctor, Berlioz was expected to follow his father into medicine, and he attended a Parisian medical college before defying his family by taking up music as a profession.

His independence of mind and refusal to follow traditional rules and formulas put him at odds with the conservative musical establishment of Paris.

He briefly moderated his style sufficiently to win France’s premier music prize – the Prix de Rome – in 1830, but he learned little from the academics of the Paris Conservatoire.

Opinion was divided for many years between those who thought him an original genius and those who viewed his music as lacking in form and coherence.

At the age of twenty-four, Berlioz fell in love with the Irish Shakespearean actress Harriet Smithson, and he pursued her obsessively until she finally accepted him seven years later.

At the age of twenty-four, Berlioz fell in love with the Irish Shakespearean actress Harriet Smithson, and he pursued her obsessively until she finally accepted him seven years later.

Their marriage was happy at first but eventually foundered. Harriet inspired his first major success, the Symphonie fantastique, in which an idealized depiction of her occurs throughout.

Berlioz completed three operas, the first of which, Benvenuto Cellini, was an outright failure. The second, the huge epic Les Troyens (The Trojans), was so large in scale that it was never staged in its entirety during his lifetime.

His last opera, Béatrice et Bénédict – based on Shakespeare’s comedy Much Ado About Nothing – was a success at its premiere but did not enter the regular operatic repertoire.

Meeting only occasional success in France as a composer, Berlioz increasingly turned to conduct, in which he gained an international reputation.

He was highly regarded in Germany, Britain, and Russia both as a composer and as a conductor.

To supplement his earnings he wrote musical journalism throughout much of his career; some of it has been preserved in book form, including his Treatise on Instrumentation (1844), which was influential in the 19th and 20th centuries. Berlioz died in Paris at the age of 65.

Life and career

1803–1821: Early years

Berlioz was born on 11 December 1803, the eldest child of Louis Berlioz (1776–1848), a physician, and his wife, Marie-Antoinette Joséphine, née Marmion (1784–1838).

His birthplace was the family home in the commune of La Côte-Saint-André in the département of Isère, in south-eastern France.

His parents had five more children, three of whom died in infancy; their surviving daughters, Nanci and Adèle, remained close to Berlioz throughout their lives.

Berlioz’s father, a respected local figure, was a progressively minded doctor credited as the first European to practice and write about acupuncture.

He was an agnostic with a liberal outlook; his wife was a strict Roman Catholic of less flexible views.

After briefly attending a local school when he was about ten, Berlioz was educated at home by his father.

He recalled in his Mémoires that he enjoyed geography, especially books about travel, to which his mind would sometimes wander when he was supposed to be studying Latin; the classics nonetheless made an impression on him, and he was moved to tears by Virgil’s account of the tragedy of Dido and Aeneas. Later he studied philosophy, rhetoric, and – because his father planned a medical career for him – anatomy.

He recalled in his Mémoires that he enjoyed geography, especially books about travel, to which his mind would sometimes wander when he was supposed to be studying Latin; the classics nonetheless made an impression on him, and he was moved to tears by Virgil’s account of the tragedy of Dido and Aeneas. Later he studied philosophy, rhetoric, and – because his father planned a medical career for him – anatomy.

Music did not feature prominently in the young Berlioz’s education. His father gave him basic instruction on the flageolet, and he later took flute and guitar lessons with local teachers.

He never studied the piano, and throughout his life played haltingly at best. He later contended that this was an advantage because it “saved me from the tyranny of keyboard habits, so dangerous to thought, and from the lure of conventional harmonies”.

At the age of twelve Berlioz fell in love for the first time. The object of his affections was an eighteen-year-old neighbor, Estelle Dubœuf. He was teased for what was seen as a boyish crush, but something of his early passion for Estelle endured all his life.

He poured some of his unrequited feelings into his early attempts at composition. Trying to master harmony, he read Rameau’s Traité de l’harmonie, which proved incomprehensible to a novice, but Charles-Simon Catel’s simpler treatise on the subject made it clearer to him.

He wrote several chamber works as a youth, subsequently destroying the manuscripts, but one theme that remained in his mind reappeared later as the A-flat second subject of the overture to Les Francs-juges.

1821–1824: Medical student

In March 1821 Berlioz passed the baccalauréat examination at the University of Grenoble – it is not certain whether at the first or second attempt – and in late September, aged seventeen, he moved to Paris.

At his father’s insistence, he enrolled at the School of Medicine of the University of Paris. He had to fight hard to overcome his revulsion at dissecting bodies, but in deference to his father’s wishes, he forced himself to continue his medical studies.

The horrors of the medical college were mitigated thanks to an ample allowance from his father, which enabled him to take full advantage of the cultural, and particularly musical, life of Paris.

Music did not at that time enjoy the prestige of literature in French culture, but Paris nonetheless possessed two major opera houses and the country’s most important music library.

Berlioz took advantage of them all. Within days of arriving in Paris, he went to the Opéra, and although the piece on offer was by a minor composer, the staging and the magnificent orchestral playing enchanted him.

He went to other works at the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique; at the former, three weeks after his arrival, he saw Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride, which thrilled him.

He was particularly inspired by Gluck’s use of the orchestra to carry the drama along. A later performance of the same work at the Opéra convinced him that his vocation was to be a composer.

The dominance of Italian opera in Paris, against which Berlioz later campaigned, was still in the future, and at the opera houses, he heard and absorbed the works of Étienne Méhul and François-Adrien Boieldieu, other operas written in the French style by foreign composers, particularly Gaspare Spontini, and above all five operas by Gluck.

He began to visit the Paris Conservatoire library in between his medical studies, seeking out scores of Gluck’s operas and making copies of parts of them.

By the end of 1822, he felt that his attempts to learn composition needed to be augmented with formal tuition, and he approached Jean-François Le Sueur, director of the Royal Chapel and professor at the Conservatoire, who accepted him as a private pupil.

In August 1823 Berlioz made the first of many contributions to the musical press: a letter to the journal Le Corsaire defending French opera against the incursions of its Italian rival.

He contended that all Rossini’s operas put together could not stand comparison with even a few bars of those of Gluck, Spontini, or Le Sueur. By now he had composed several works including Estelle et Némorin and Le Passage de la Mer Rouge (The Crossing of the Red Sea) – both since lost.

In 1824 Berlioz graduated from medical school, after which he abandoned medicine, to the strong disapproval of his parents.

His father suggested law as an alternative profession and refused to countenance music as a career.

He reduced and sometimes withheld his son’s allowance, and Berlioz went through some years of financial hardship.

1824–1830: Conservatoire student

In 1824 Berlioz composed a Messe solennelle. It was performed twice, after which he suppressed the score, which was thought lost until a copy was discovered in 1991.

During 1825 and 1826 he wrote his first opera, Les Francs-juges, which was not performed and survives only in fragments, the best known of which is the overture.

In later works, he reused parts of the score, such as the “March of the Guards”, which he incorporated four years later in the Symphonie fantastique as the “March to the Scaffold”.

n August 1826 Berlioz was admitted as a student to the Conservatoire, studying composition under Le Sueur and counterpoint and fugue with Anton Reicha.

In the same year, he made the first of four attempts to win France’s premier music prize, the Prix de Rome, and was eliminated in the first round.

The following year, to earn some money, he joined the chorus at the Théâtre des Nouveautés.

He competed again for the Prix de Rome, submitting the first of his Prix cantatas, La Mort d’Orphée, in July.

Later that year he attended productions of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet at the Théâtre de l’Odéon given by Charles Kemble’s touring company.

Although at the time Berlioz spoke hardly any English, he was overwhelmed by the plays – the start of a lifelong passion for Shakespeare.

He also conceived a passion for Kemble’s leading lady, Harriet Smithson – his biographer Hugh Macdonald calls it “emotional derangement” – and obsessively pursued her, without success, for several years. She refused even to meet him.

The first concert of Berlioz’s music took place in May 1828, when his friend Nathan Bloc conducted the premieres of the overtures Les Francs-juges and Waverley and other works. The hall was far from full, and Berlioz lost money.

Nevertheless, he was greatly encouraged by the vociferous approval of his performers, and the applause from musicians in the audience, including his Conservatoire professors, the directors of the Opéra and Opéra-Comique, and the composers Auber and Hérold.

Berlioz’s fascination with Shakespeare’s plays prompted him to start learning English in 1828 so that he could read them in the original. At around the same time he encountered two further creative inspirations: Beethoven and Goethe.

He heard Beethoven’s third, fifth and seventh symphonies performed at the Conservatoire, and read Goethe’s Faust in Gérard de Nerval’s translation.

Beethoven became both an ideal and an obstacle for Berlioz – an inspiring predecessor but a daunting one.

Goethe’s work was the basis of Huit scènes de Faust (Berlioz’s Opus 1), premiered the following year and reworked and expanded much later as La Damnation de Faust.

1830–1832: Prix de Rome

Berlioz was largely apolitical, and neither supported nor opposed the July Revolution of 1830, but when it broke out he found himself in the middle of it. He recorded events in his Mémoires:

I was finishing my cantata when the revolution broke out … I dashed off the final pages of my orchestral score to the sound of stray bullets coming over the roofs and pattering on the wall outside my window. On the 29th I had finished and was free to go out and roam about Paris till morning, pistol in hand.

The cantata was La Mort de Sardanapale, with which he won the Prix de Rome. His entry the previous year, Cléopâtre, had attracted disapproval from the judges because to highly conservative musicians it “betrayed dangerous tendencies”, and for his 1830 offering, he carefully modified his natural style to meet official approval.

During the same year, he wrote the Symphonie fantastique and became engaged to be married.

By now recoiling from his obsession with Smithson, Berlioz fell in love with a nineteen-year-old pianist, Marie (“Camille”) Moke.

His feelings were reciprocated, and the couple planned to be married.

In December Berlioz organized a concert at which the Symphonie fantastique was premiered.

Protracted applause followed the performance, and the press reviews expressed both the shock and the pleasure the work had given.

Berlioz’s biographer David Cairns calls the concert a landmark not only in the composer’s career but in the evolution of the modern orchestra.

Franz Liszt was among those attending the concert; this was the beginning of a long friendship. Liszt later transcribed the entire Symphonie fantastique for piano to enable more people to hear it.

Shortly after the concert, Berlioz set off for Italy: under the terms of the Prix de Rome, winners studied for two years at the Villa Medici, the French Academy in Rome.

Within three weeks of his arrival, he went absent without leave: he had learned that Marie had broken off their engagement and was to marry an older and richer suitor, Camille Pleyel, the heir to the Pleyel piano manufacturing company.

Berlioz made an elaborate plan to kill them both (and her mother, known to him as “l’hippopotame”), and acquired poisons, pistols, and a disguise for the purpose.

By the time he reached Nice on his journey to Paris, he thought better of the scheme, abandoned the idea of revenge, and successfully sought permission to return to the Villa Medici.

He stayed for a few weeks in Nice and wrote his King Lear overture. On the way back to Rome he began work on a piece for narrator, solo voices, chorus, and orchestra, Le Retour à la vie (The Return to Life, later renamed Lélio), a sequel to the Symphonie fantastique.

Berlioz took little pleasure in his time in Rome. His colleagues at the Villa Medici, under their benevolent principal Horace Vernet, made him welcome, and he enjoyed his meetings with Felix Mendelssohn, who was visiting the city, but he found Rome distasteful: “the most stupid and prosaic city I know; it is no place for anyone with head or heart.”

Nonetheless, Italy had an important influence on his development. He visited many parts of it during his residency in Rome.

Macdonald comments that after his time there, Berlioz had “a new color and glow in his music … sensuous and vivacious” – derived not from Italian painting, in which he was uninterested, or Italian music, which he despised, but from “the scenery and the sun, and from his acute sense of locale”.

Macdonald identifies Harold in Italy, Benvenuto Cellini, and Roméo et Juliette as the most obvious expressions of his response to Italy, and adds that Les Troyens and Béatrice et Bénédict “reflect the warmth and stillness of the Mediterranean, as well as its vivacity and force”.

Berlioz himself wrote that Harold in Italy drew on “the poetic memories formed from my wanderings in Abruzzi”.

Vernet agreed to Berlioz’s request to be allowed to leave the Villa Medici before the end of his two-year term. Heeding Vernet’s advice that it would be prudent to delay his return to Paris, where the Conservatoire authorities might be less indulgent about the premature ending of his studies, he made a leisurely journey back, detouring via La Côte-Saint-André to see his family. He left Rome in May 1832 and arrived in Paris in November.

1832–1840: Paris

On 9 December 1832 Berlioz presented a concert of his works at the Conservatoire.

The program included the overture of Les Francs-juges, the Symphonie fantastique – extensively revised since its premiere – and Le Retour à la vie, in which Bocage, a popular actor, declaimed the monologues.

Through a third party, Berlioz had sent an invitation to Harriet Smithson, who accepted, and was dazzled by the celebrities in the audience.

Among the musicians present were Liszt, Frédéric Chopin and Niccolò Paganini; writers included Alexandre Dumas, Théophile Gautier, Heinrich Heine, Victor Hugo and George Sand.

The concert was such a success that the program was repeated within the month, but the more immediate consequence was that Berlioz and Smithson finally met.

By 1832 Smithson’s career was in decline. She presented a ruinously unsuccessful season, first at the Théâtre-Italien and then at lesser venues, and by March 1833 she was deep in debt.

Biographers differ about whether and to what extent Smithson’s receptiveness to Berlioz’s wooing was motivated by financial considerations, but she accepted him and in the face of strong opposition from both their families they were married at the British Embassy in Paris on 3 October 1833.

The couple lived first in Paris, and later in Montmartre (then still a village). On 14 August 1834 their only child, Louis-Clément-Thomas, was born.

The first few years of the marriage were happy, although it eventually foundered.

Harriet continued to yearn for a career but, as her biographer Peter Raby comments, she never learned to speak French fluently, which seriously limited both her professional and her social life.

Paganini, known chiefly as a violinist, had acquired a Stradivarius viola, which he wanted to play in public if he could find the right music.

Greatly impressed by the Symphonie fantastique, he asked Berlioz to write him a suitable piece.

Berlioz told him that he could not write a brilliantly virtuoso work, and began composing what he called a symphony with viola obbligato, Harold in Italy.

As he foresaw, Paganini found the solo part too reticent – “There’s not enough for me to do here; I should be playing all the time” – and the violist at the premiere in November 1834 was Chrétien Urhan.

Until the end of 1835, Berlioz had a modest stipend as a laureate of the Prix de Rome.

His earnings from composing were neither substantial nor regular, and he supplemented them by writing music criticism for the Parisian press.

Macdonald comments that this was an activity “at which he excelled but which he abhorred”.

He wrote for L’Europe littéraire (1833), Le Rénovateur (1833–1835), and from 1834 for the Gazette musicale and the Journal des débats.

He was the first, but not the last, prominent French composer to double as a reviewer: among his successors were Fauré, Messager, Dukas, and Debussy.

Although he complained – both privately and sometimes in his articles – that his time would be better spent writing music than in writing music criticism, he was able to indulge himself in attacking his bêtes noires and extolling his enthusiasms.

The former included musical pedants, coloratura writing and singing, viola players who were merely incompetent violinists, inane libretti, and baroque counterpoint.

He extravagantly praised Beethoven’s symphonies, Gluck’s and Weber’s operas, and scrupulously refrained from promoting his own compositions.

His journalism consisted mainly of music criticism, some of which he collected and published, such as Evenings in the Orchestra (1854), but also more technical articles, such as those that formed the basis of his Treatise on Instrumentation (1844).

Despite his complaints, Berlioz continued writing music criticism for most of his life, long after he had any financial need to do so.

Berlioz secured a commission from the French government for his Requiem – the Grande Messe des morts – first performed at Les Invalides in December 1837.

A second government commission followed – the Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale in 1840. Neither work brought him much money or artistic fame at the time, but the Requiem held a special place in his affections: “If I were threatened with the destruction of the whole of my works save one, I would crave mercy for the Messe des morts”.

One of Berlioz’s main aims in the 1830s was “battering down the doors of the Opéra”.

In Paris at this period, the musical success that mattered was in the opera house and not the concert hall.

Robert Schumann commented, “To the French, music by itself means nothing”.

Berlioz worked on his opera Benvenuto Cellini from 1834 until 1837, continually distracted by his increasing activities as a critic and as a promoter of his own symphonic concerts.

The Berlioz scholar D. Kern Holoman comments that Berlioz rightly regarded Benvenuto Cellini as a work of exceptional exuberance and verve, deserving a better reception than it received.

Holoman adds that the piece was of “surpassing technical difficulty”, and that the singers were not especially cooperative.

A weak libretto and unsatisfactory staging exacerbated the poor reception. The opera had only four complete performances, three in September 1838 and one in January 1839.

Berlioz said that the failure of the piece meant that the doors of the Opéra were closed to him for the rest of his career – which they were, except for a commission to arrange a Weber score in 1841.

Shortly after the failure of the opera, Berlioz had great success as composer-conductor of a concert at which Harold in Italy was given again.

This time Paganini was present in the audience; he came onto the platform at the end and knelt in homage to Berlioz and kissed his hand.

A few days later Berlioz was astonished to receive a cheque from him for 20,000 francs.

Paganini’s gift enabled Berlioz to pay off Harriet’s and his own debts, give up music criticism for the time being, and concentrate on composition.

He wrote the “dramatic symphony” Roméo et Juliette for voices, chorus and orchestra. It was premiered in November 1839 and was so well received that Berlioz and his huge instrumental and vocal forces gave two further performances in rapid succession.

Among the audiences was the young Wagner, who was overwhelmed by its revelation of the possibilities of musical poetry, and who later drew on it when composing Tristan und Isolde.

At the close of the decade, Berlioz achieved official recognition in the form of appointment as deputy librarian of the Conservatoire and as an officer of the Legion of Honour.

The former was an undemanding post, but not highly paid, and Berlioz remained in need of a reliable income to allow him the leisure for composition.

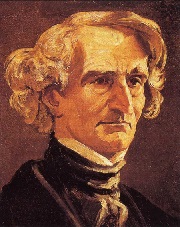

Berlioz in 1845

The Symphonie funèbre et triomphale, marking the tenth anniversary of the 1830 Revolution, was performed in the open air under the direction of the composer in July 1840.

The following year the Opéra commissioned Berlioz to adapt Weber’s Der Freischütz to meet the house’s rigid requirements: he wrote recitatives to replace the spoken dialogue and orchestrated Weber’s Invitation to the Dance to provide the obligatory ballet music.

In the same year, he completed settings of six poems by his friend Théophile Gautier, which formed the song cycle Les Nuits d’été (with piano accompaniment, later orchestrated).

He also worked on a projected opera, La Nonne sanglante (The Bloody Nun), to a libretto by Eugène Scribe, but made little progress.

In November 1841 he began publishing a series of sixteen articles in the Revue et gazette musicale giving his views about orchestration; they were the basis of his Treatise on Instrumentation, published in 1843.

During the 1840s Berlioz spent much of his time making music outside France. He struggled to make money from his concerts in Paris, and learning of the large sums made by promoters from performances of his music in other countries, he resolved to try conducting abroad.

He began in Brussels, giving two concerts in September 1842. An extensive German tour followed: in 1842 and 1843 he gave concerts in twelve German cities.

His reception was enthusiastic. The German public was better disposed than the French to his innovative compositions, and his conducting was seen as highly impressive.

During the tour, he had enjoyable meetings with Mendelssohn and Schumann in Leipzig, Wagner in Dresden, and Meyerbeer in Berlin.

By this time Berlioz’s marriage was failing. Harriet resented his celebrity and her own eclipse, and as Raby puts it, “possessiveness turned to suspicion and jealousy as Berlioz became involved with the singer Marie Recio”.

Harriet’s health deteriorated, and she took to drinking heavily. Her suspicion about Recio was well founded: the latter became Berlioz’s mistress in 1841 and accompanied him on his German tour.

Berlioz returned to Paris in mid-1843. During the following year, he wrote two of his most popular short works, the overtures Le Carnaval Romain (reusing music from Benvenuto Cellini) and Le Corsaire (originally called La tour de Nice).

Towards the end of the year, he and Harriet separated. Berlioz maintained two households: Harriet remained in Montmartre and he moved in with Recio at her flat in central Paris. His son Louis was sent to a boarding school in Rouen.

Foreign tours featured prominently in Berlioz’s life during the 1840s and 1850s.

Not only were they highly rewarding both artistically and financially, but he did not have to grapple with the administrative problems of promoting concerts in Paris. Macdonald comments:

The more he traveled the more bitter he became about conditions at home; yet though he contemplated settling abroad – in Dresden, for instance, and in London – he always went back to Paris.

Berlioz’s major work from the decade was La Damnation de Faust. He presented it in Paris in December 1846, but it played to half-empty houses, despite excellent reviews, some from critics not usually well disposed to his music.

The highly romantic subject was out of step with the times, and one sympathetic reviewer observed that there was an unbridgeable gap between the composer’s conception of art and that of the Paris public.

The failure of the piece left Berlioz heavily in debt; he restored his finances the following year with the first of two highly remunerative trips to Russia.

His other foreign tours during the rest of the 1840s included Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, and Germany.

After those came the first of his five visits to England; it lasted for more than seven months (November 1847 to July 1848).

His reception in London was enthusiastic, but the visit was not a financial success because of mismanagement by his impresario, the conductor Louis-Antoine Jullien.

Soon after Berlioz’s return to Paris in mid-September 1848, Harriet suffered a series of strokes, which left her almost paralyzed. She needed constant nursing, which he paid for. When in Paris he visited her continually, sometimes twice a day.

The 1850s: International success

After the failure of La Damnation de Faust, Berlioz spent less time on composition during the next eight years.

He wrote a Te Deum, completed in 1849 but not published until 1855, and some short pieces.

His most substantial work between The Damnation and his epic Les Troyens (1856–1858) was a “sacred trilogy”, L’Enfance du Christ (Christ’s Childhood), which he began in 1850.

In 1851 he was at the Great Exhibition in London as a member of an international committee judging musical instruments.

He returned to London in 1852 and 1853, conducting his own works and others. He enjoyed consistent success there, with the exception of a revival of Benvenuto Cellini at Covent Garden which was withdrawn after one performance.

The opera was presented in Leipzig in 1852 in a revised version prepared by Liszt with Berlioz’s approval and was moderately successful.

In the early years of the decade, Berlioz made numerous appearances in Germany as a conductor.

In 1854 Harriet died.

Both Berlioz and their son Louis had been with her shortly before her death.

During the year Berlioz completed the composition of L’Enfance du Christ, worked on his book of memoirs, and married Marie Recio, which, he explained to his son, he felt it his duty to do after living with her for so many years.

At the end of the year, the first performance of L’Enfance du Christ was warmly received, to his surprise. He spent much of the next year in conducting and writing prose.

During Berlioz’s German tour in 1856, Liszt and his companion, Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, encouraged Berlioz’s tentative conception of an opera based on the Aeneid.

Having first completed the orchestration of his 1841 song cycle Les Nuits d’été, he began work on Les Troyens – The Trojans – writing his own libretto based on Virgil’s epic.

He worked on it, in between his conducting commitments, for two years. In 1858 he was elected to the Institut de France, an honor he had long sought, though he played down the importance he attached to it.

In the same year, he completed Les Troyens. He then spent five years trying to have it staged.

1860–1869: Final years

In June 1862 Berlioz’s wife died suddenly, aged 48. She was survived by her mother, to whom Berlioz was devoted, and who looked after him for the rest of his life.

Les Troyens – a five-act, five-hour opera – was on too large a scale to be acceptable to the management of the Opéra, and Berlioz’s efforts to have it staged there failed.

The only way he could find of seeing the work produced was to divide it into two parts: “The Fall of Troy” and “The Trojans at Carthage”.

The latter, consisting of the final three acts of the original, was presented at the Théâtre‐Lyrique, Paris, in November 1863, but even that truncated version was further truncated: during the run of 22 performances, number after number was cut. The experience demoralized Berlioz, who wrote no more music after this.

Berlioz did not seek a revival of Les Troyens and none took place for nearly 30 years.

He sold the publishing rights for a large sum, and his last years were financially comfortable; he was able to give up his work as a critic, but he lapsed into depression. As well as losing both his wives, he had lost both his sisters, and he became morbidly aware of death as many of his friends and other contemporaries died.

He and his son had grown deeply attached to each other, but Louis was a captain in the merchant navy and was more often than not away from home.

Berlioz’s physical health was not good, and he was often in pain from an intestinal complaint, possibly Crohn’s disease.

After the death of his second wife, Berlioz had two romantic interludes.

During 1862 he met – probably in the Montmartre Cemetery – a young woman less than half his age, whose first name was Amélie and whose second, possibly married, name is not recorded.

Almost nothing is known about their relationship, which lasted for less than a year.

After they ceased to meet, Amélie died, aged only 26.

Berlioz was unaware of it until he came across her grave six months later.

Cairns hypothesizes that the shock of her death prompted him to seek out his first love, Estelle, now a widow aged 67.

He called on her in September 1864; she received him kindly, and he visited her in three successive summers; he wrote to her nearly every month for the rest of his life.

In 1867 Berlioz received the news that his son had died in Havana of yellow fever.

Macdonald suggests that Berlioz may have sought distraction from his grief by going ahead with a planned series of concerts in St Petersburg and Moscow, but far from rejuvenating him, the trip sapped his remaining strength.

The concerts were successful, and Berlioz received a warm response from the new generation of Russian composers and the general public, but he returned to Paris visibly unwell.

He went to Nice to recuperate in the Mediterranean climate, but fell on rocks by the shore, possibly because of a stroke, and had to return to Paris, where he convalesced for several months.

In August 1868, he felt able to travel briefly to Grenoble to judge a choral festival.

After arriving back in Paris he gradually grew weaker and died at his house in the Rue de Calais on 8 March 1869, at the age of 65. He was buried in Montmartre Cemetery with his two wives, who were exhumed and re-buried next to him.

Works

In his 1983 book The Musical Language of Berlioz, Julian Rushton asks “where Berlioz comes in the history of musical forms and what is his progeny”. Rushton’s answers to these questions are “nowhere” and “none”.

He cites well-known studies of musical history in which Berlioz is mentioned only in passing or not at all, and suggests that this is partly because Berlioz had no models among his predecessors and was a model to none of his successors.

“In his works, as in his life, Berlioz was a lone wolf”.

Forty years earlier, Sir Thomas Beecham, a lifelong proponent of Berlioz’s music, commented similarly, writing that although, for example, Mozart was a greater composer, his music drew on the works of his predecessors, whereas Berlioz’s works were all wholly original: “the Symphonie fantastique or La Damnation de Faust broke upon the world like some unaccountable effort of spontaneous generation which had dispensed with the machinery of normal parentage”.

Rushton suggests that “Berlioz’s way is neither architectural nor developmental, but illustrative”.

He judges this to be part of a continuing French musical aesthetic, favoring a “decorative” – rather than the German “architectural” – approach to composition.

Abstraction and discursiveness are alien to this tradition, and in operas, and to a large extent in orchestral music, there is little continuous development; instead, self-contained numbers or sections are preferred.

Berlioz’s compositional techniques have been strongly criticized and equally strongly defended.

It is common ground for critics and defenders that his approach to harmony and musical structure conforms to no established rules; his detractors ascribe this to ignorance, and his proponents to independent-minded adventurousness.

His approach to rhythm caused perplexity to conservatively-inclined contemporaries; he hated the phrase carrée – the unvaried four- or eight-bar phrase – and introduced new varieties of rhythm to his music.

He explained his practice in an 1837 article: accenting weak beats at the expense of the strong, alternating triple and duple groups of notes, and using unexpected rhythmic themes independent of the main melody.

Macdonald writes that Berlioz was a natural melodist, but that his rhythmic sense led him away from regular phrase lengths; he “spoke naturally in a kind of flexible musical prose, with surprise and contour important elements”.

Berlioz’s approach to harmony and counterpoint was idiosyncratic and has provoked adverse criticism.

Pierre Boulez commented, “There are awkward harmonies in Berlioz that make one scream”.

In Rushton’s analysis, most of Berlioz’s melodies have “clear tonal and harmonic implications” but the composer sometimes chose not to harmonize accordingly.

Rushton observes that Berlioz’s preference for irregular rhythm subverts conventional harmony: “Classic and romantic melody usually implies harmonic motion of some consistency and smoothness; Berlioz’s aspiration to musical prose tends to resist such consistency.”

The pianist and musical analyst Charles Rosen has written that Berlioz often sets the climax of his melodies in relief with the most emphatic chord a triad in root position, and often a tonic chord where the melody leads the listener to expect a dominant.

He gives as an example the second phrase of the main theme – the idée fixe – of the Symphonie fantastique, “famous for its shock to classical sensibilities”, in which the melody implies a dominant at its climax resolved by a tonic, but in which Berlioz anticipates the resolution by putting a tonic under the climactic note.

Even among those unsympathetic to his music, few deny that Berlioz was a master of orchestration.

Richard Strauss wrote that Berlioz invented the modern orchestra.

Some of those who recognize Berlioz’s mastery of orchestration nonetheless dislike a few of his more extreme effects. The pedal point for trombones in the “Hostias” section of the Requiem is often cited; some musicians such as Gordon Jacob have found the effect unpleasant.

Macdonald has questioned Berlioz’s fondness for divided cellos and basses in dense, low chords, but he emphasizes that such contentious points are rare compared with “the felicities and masterstrokes” abounding in the scores.

Berlioz took instruments hitherto used for special purposes and introduced them into his regular orchestra: Macdonald mentions the harp, the cor anglais, the bass clarinet, and the valve trumpet.

Among the characteristic touches in Berlioz’s orchestration singled out by Macdonald is the wind “chattering on repeated notes” for brilliance, or being used to add “somber color” to Romeo’s arrival at the Capulets’ vault, and the “Chœur d’ombres” in Lélio. Of Berlioz’s brass he writes:

Brass can be solemn or brazen; the “Marche au supplice” in the Symphonie fantastique is a defiantly modern use of brass. Trombones introduce Mephistopheles with three flashing chords or support the gloomy doubts of Narbal in Les Troyens. With a hiss of cymbals, pianissimo, they mark the entry of the Cardinal in Benvenuto Cellini and the blessing of little Astyanax by Priam in Les Troyens.

Symphonies

Berlioz wrote four large-scale works he called symphonies, but his conception of the genre differed greatly from the classical pattern of the German tradition.

With rare exceptions, such as Beethoven’s Ninth, a symphony was taken to be a large‐scale wholly orchestral work, usually in four movements, using sonata form in the first movement and sometimes in others.

Some pictorial touches were included in symphonies by Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and others, but the symphony was not customarily used to recount a narrative.

All four of Berlioz’s symphonies differ from the contemporary norm. The first, the Symphonie fantastique (1830), is purely orchestral, and the opening movement is broadly in sonata form, but the work tells a story, graphically and specifically.

The recurring idée fixe theme is the composer’s idealized (and in the last movement caricatured) portrait of Harriet Smithson. Schumann wrote of the work that despite its apparent formlessness, “there is an inherent symmetrical order corresponding to the great dimensions of the work, and this besides the inner connexions of thought”, and in the 20th century Constant Lambert wrote, “Formally speaking it is among the finest of 19th-century symphonies”. The work has always been among Berlioz’s most popular.

Harold in Italy, despite its subtitle “Symphony in four parts with viola principal”, is described by the musicologist Mark Evan Bonds as a work traditionally seen as lacking any direct historical antecedent, “a hybrid of symphony and concerto that owes little or nothing to the earlier, lighter genre of the symphonie concertante”.

In the 20th century, critical opinion varied about the work, even among those well-disposed to Berlioz. Felix Weingartner, an early 20th century champion of the composer, wrote in 1904 that it did not reach the level of the Symphonie fantastique; fifty years later Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor found it “romantic and picturesque … Berlioz at his best”.

In the 21st century Bonds ranks it among the greatest works of its kind in the 19th century.

The “Dramatic Symphony” with a chorus, Roméo et Juliette, is still further from the traditional symphonic model.

The episodes of Shakespeare’s drama are represented in orchestral music, interspersed with expository and narrative sections for voices.

Among Berlioz’s admirers, the work divides opinion. Weingartner called it “a style-less mixture of different forms; not quite oratorio, not quite an opera, not quite a symphony – fragments of all three, and nothing perfect”.

Countering accusations of lack of unity in this and other Berlioz works, Emmanuel Chabrier replied in a single emphatic word.

Cairns regards the work as symphonic, albeit “a bold extension” of the genre, but he notes that other Berliozians including Wilfrid Mellers view it as “a curious, not entirely convincing compromise between symphonic and operatic techniques”.

Rushton comments that “pronounced unity” is not among the virtues of the work, but he argues that to close one’s mind on that account is to miss all that the music has to give.

The last of the four symphonies is the Symphonie funebre et triomphale, for giant brass and woodwind band (1840), with string parts added later, together with an optional chorus.

The structure is more conventional than the instrumentation: the first movement is in sonata form, but there are only two other movements, and Berlioz did not adhere to the traditional relationship between the various keys of the piece.

Wagner called the symphony “popular in the most ideal sense … every urchin in a blue blouse would thoroughly understand it”.

Operas

None of Berlioz’s three completed operas were written to commission, and theatre managers were not enthusiastic about staging them.

Cairns writes that unlike Meyerbeer, who was rich, influential, and deferred to by opera management, Berlioz was “an opera composer on sufferance, one who composed on borrowed time paid for with money that was not his but lent by a wealthy friend”.

The three operas contrast strongly with one another.

The first, Benvenuto Cellini (1838), inspired by the memoirs of the Florentine sculptor, is an opera semiseria, seldom staged until the 21st century, when there have been signs of a revival in its fortunes, with its first production at the Metropolitan Opera (2003) and a co-production by the English National Opera and the Opéra national de Paris (2014), but it remains the least often produced of the three operas.

n 2008, the music critic Michael Quinn called it “an opera overflowing in every way, with musical gold bursting from each curve and crevice … a score of continually stupendous brilliance and invention” but agreed with the general view of the libretto: “incoherent … episodic, too epic to be a comedy, too ironic for tragedy”.

Berlioz welcomed Liszt’s help in revising the work, streamlining the confusing plot; for his other two operas, he wrote his own libretti.

The epic Les Troyens (1858) is described by the musical scholar James Haar as “incontestably Berlioz’s masterpiece”, a view shared by many other writers.

Berlioz based the text on Virgil’s Aeneid, depicting the fall of Troy and the subsequent travels of the hero. Holoman describes the poetry of the libretto as old-fashioned for its day, but effective and at times beautiful.

The opera consists of a series of self-contained numbers, but they form a continuous narrative, with the orchestra playing a vital part in expounding and commenting on the action.

Although the work plays for five hours (including intervals) it is no longer the normal practice to present it across two evenings.

Les Troyens, in Holoman’s view, embodies the composer’s artistic creed: the union of music and poetry holds “incomparably greater power than either art alone”.

The last of Berlioz’s operas is the Shakespearean comedy Béatrice et Bénédict (1862), written, the composer said, as a relaxation after his efforts with Les Troyens. He described it as “a caprice written with the point of a needle”.

His libretto, based on Much Ado About Nothing, omits Shakespeare’s darker sub-plots and replaces the clowns Dogberry and Verges with an invention of his own, the tiresome and pompous music master Somarone.

The action focuses on the sparring between the two leading characters, but the score contains some gentler music, such as the nocturne-duet “Nuit paisible et sereine”, the beauty of which, Cairns suggests, matches or surpasses the love music in Roméo or Les Troyens.

Cairns writes that Béatrice et Bénédict “has wit and grace and lightness of touch. It accepts life as it is. The opera is a divertissement, not a grand statement”.

La Damnation de Faust, although not written for the theatre, is sometimes staged as an opera.

Choral

Berlioz gained a reputation, only partly justified, for liking gigantic orchestral and choral forces. In France there was a tradition of open-air performance, dating from the Revolution, calling for larger ensembles than were needed in the concert hall.

Among the generation of French composers ahead of him, Cherubini, Méhul, Gossec, and Berlioz’s teacher Le Sueur all wrote for huge forces on occasion, and in the Requiem and to a lesser degree the Te Deum Berlioz follows them, in his own manner.

The Requiem calls for sixteen timpani, quadruple woodwind, and twelve horns, but the moments when the full orchestral sound is unleashed are few – the Dies Irae is one such – and most of the Requiem is notable for its restraint.

The orchestra does not play at all in the “Quaerens me” section, and what Cairns calls “the apocalyptic armory” is reserved for special moments of color and emphasis: “its purpose is not merely spectacular but architectural, to clarify the musical structure and open up multiple perspectives.”

What Macdonald calls Berlioz’s monumental manner is more prominent in the Te Deum, composed in 1849 and first heard in 1855 when it was given in connection with the Exposition Universelle.

By that time the composer had added to its two choruses a part for massed children’s voices, inspired by hearing a choir of 6,500 children singing in St Paul’s Cathedral during his London trip in 1851.

A cantata for double chorus and large orchestra in honor of Napoleon III, L’Impériale, described by Berlioz as “en style énorme”, was played several times at the 1855 exhibition, but has subsequently remained a rarity.

La Damnation de Faust, though conceived as a work for the concert hall, did not achieve success in France until it was staged as an opera long after the composer’s death.

Within a year of Raoul Gunsbourg’s production of the piece at Monte Carlo in 1893, the work was presented as an opera in Italy, Germany, Britain, Russia, and the US.

The many elements of the work vary from the robust “Hungarian March” near the beginning to the delicate “Dance of the Sylphs”, the frenetic “Ride to the Abyss”, Méphistophélès’ suave and seductive “Song of the Devil”, and Brander’s “Song of a Rat”, a requiem for a dead rodent.

L’Enfance du Christ (1850–1854) follows the pattern of La Damnation de Faust in mixing dramatic action and philosophic reflection. Berlioz, after a brief youthful religious spell, was a lifelong agnostic, but he was not hostile to the Roman Catholic church, and Macdonald calls the “serenely contemplative” end of the work “the nearest Berlioz ever came to a devoutly Christian mode of expression”.

Mélodies

Berlioz wrote songs throughout his career, but not prolifically. His best-known work in the genre is the song cycle Les Nuits d’été, a group of six songs, originally for voice and piano but now usually heard in its later orchestrated form.

He suppressed some of his early songs, and his last publication, in 1865, was the 33 Mélodies, collecting into one volume all the songs that he chose to preserve.

Some of them, such as “Hélène” and “Sara la baigneuse”, exist in versions for four voices with accompaniment, and there are others for two or three voices.

Berlioz later orchestrated some of the songs originally written with piano accompaniment, and some, such as “Zaïde” and “Le Chasseur danois” were written with alternative piano or orchestral parts.

“La Captive”, to words by Victor Hugo, exists in six different versions. In its final version (1849) it was described by the Berlioz scholar Tom S. Wotton as “a miniature symphonic poem”.]

The first version, written at the Villa Medici, had been in a fairly regular rhythm, but for his revision, Berlioz made the strophic outline less clear-cut and added optional orchestral parts for the last stanza, which brings the song to a quiet close.

The songs remain on the whole among the least known of Berlioz’s works, and John Warrack suggests that Schumann identified why this might be so: the shape of the melodies is, as usual with Berlioz, not straightforward, and to those used to the regular four-bar phrases of French (or German) song this is an obstacle to appreciation.

Warrack also comments that the piano parts, though not lacking in harmonic interest, are discernibly written by a non-pianist.

Despite that, Warrack considers up to a dozen songs from the 33 Mélodies well worth exploring – “Among them are some masterpieces.”

Prose

Berlioz’s literary output was considerable and mostly consisted of music criticism.

Some were collected and published in book form. His Treatise on Instrumentation (1844) began as a series of articles and remained a standard work on orchestration throughout the 19th century; when Richard Strauss was commissioned to revise it in 1905 he added new material but did not change Berlioz’s original text.

The revised form remained widely used well into the 20th century; a new English translation was published in 1948.

Other selections from Berlioz’s press columns were published in Les Soirées de l’orchestre (Evenings with the Orchestra, 1852), Les Grotesques de la musique (1859), and À travers chants (Through Songs, 1862).

His Mémoires were published posthumously in 1870. Macdonald comments that there are few facets of musical practice of the time untouched in Berlioz’s feuilletons.

He professed to dislike writing his press pieces, and they undoubtedly took up time that he would have preferred to spend writing music.

His excellence as a witty and perceptive critic may have worked to his disadvantage in another way: he became so well known to the French public in that capacity that his stature as a composer became correspondingly more difficult to establish.

Reputation and Berlioz scholarship

The first biography of Berlioz, by Eugène de Mirecourt, was published during the composer’s lifetime.

Holoman lists six other French biographies of the composer published in the four decades after his death.

Of those who wrote for and against Berlioz’s music in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, among the most outspoken were musical amateurs such as the lawyer and diarist George Templeton Strong, who called the composer’s music variously “flatulent”, “rubbish”, and “the work of a tipsy chimpanzee”, and, in the pro-Berlioz camp, the poet and journalist Walter J. Turner, who wrote what Cairns calls “exaggerated eulogies”.

Like Strong, Turner was, in the words of the music critic Charles Reid, “unhampered by any excess of technical knowledge”.

Serious studies of Berlioz in the 20th century began with Adolphe Boschot’s L’Histoire d’un romantique (three volumes, 1906–1913).

His successors were Tom S. Wotton, author of a 1935 biography, and Julien Tiersot, who wrote numerous scholarly articles on Berlioz and began the collection and editing of the composer’s letters, a process eventually completed in 2016, eighty years after Tiersot’s death.

In the early 1950s, the best-known Berlioz scholar was Jacques Barzun, a protégé of Wotton, and, like him, strongly hostile to many of Boschot’s conclusions, which they saw as unfairly critical of the composer.

Barzun’s study was published in 1950. He was accused at the time by the musicologist Winton Dean of being excessively partisan, and refusing to admit failings and unevenness in Berlioz’s music; more recently he has been credited by the musicologist Nicholas Temperley with playing a major part in improving the climate of musical opinion towards Berlioz.

Since Barzun, the leading Berlioz scholars have included David Cairns, D. Kern Holoman, Hugh Macdonald, and Julian Rushton.

Cairns translated and edited Berlioz’s Mémoires in 1969, and published a two-volume, 1500-page study of the composer (1989 and 1999), described in Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians as “one of the masterpieces of modern biography”.

Holoman was responsible for the publication in 1987 of the first thematic catalog of Berlioz’s works; two years later he published a single-volume biography of the composer.

Macdonald was appointed in 1967 as the inaugural general editor of the New Berlioz Edition published by Bärenreiter; 26 volumes were issued between 1967 and 2006 under his editorship. He is also one of the editors of Berlioz’s Correspondance générale, and author of a 1978 study of Berlioz’s orchestral music, and the Grove article on the composer.

Rushton has published two volumes of analyses of Berlioz’s music (1983 and 2001). The critic Rosemary Wilson said of his work, “He has done more than any other writer to explain the uniqueness of Berlioz’s musical style without losing a sense of wonder in its originality of musical expression.”

Changing reputation

No other composer is so controversial as Hector Berlioz. Feelings about the merits of his music are seldom lukewarm; it has always tended to excite either uncritical admiration or unfair disparagement.

The Record Guide, 1955.

Because few of Berlioz’s works were often performed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, widely accepted views of his music were based on hearsay rather than on the music itself.

The orthodox opinion emphasized supposed technical defects in the music and ascribed to the composer characteristics that he did not possess.

Debussy called him “a monster … not a musician at all. He creates the illusion of music by means borrowed from literature and painting”. In 1904, in the second edition of Grove, Henry Hadow made this judgment:

The remarkable inequality of his composition may be explained, at any rate in part, as the work of a vivid imagination striving to explain itself in a tongue that he never perfectly understood.

By the 1950s the critical climate was changing, although in 1954 the fifth edition of Grove carried this verdict from Léon Vallas:

Berlioz, in truth, never did contrive to express what he aimed at in the impeccable manner he desired. His boundless artistic ambition was nourished by no more than a melodic gift of no great amplitude, clumsy harmonic procedures, and a pen without pliancy.

Cairns dismisses the article as “an astonishing anthology of all the nonsense that has ever been talked about [Berlioz]”, but adds that by the 1960s it seemed a quaint survival from a vanished age.

By 1963 Cairns, viewing Berlioz’s greatness as firmly established, felt able to advise anyone writing on the subject, “Do not keep harping on the ‘strangeness’ of Berlioz’s music; you will no longer carry the reader with you. And do not use phrases like ‘genius without talent’, ‘a certain strain of amateurishness’, ‘curiously uneven’: they have had their day.”

One important reason for the steep rise in Berlioz’s reputation and popularity is the introduction of the LP record after the Second World War.

In 1950 Barzun made the point that although Berlioz was praised by his artistic peers, including Schumann, Wagner, Franck, and Mussorgsky, the public had heard little of his music until recordings became widely available.

Barzun maintained that many myths had grown up about the supposed quirkiness or ineptitude of the music – myths that were dispelled once the works were finally made available for all to hear.

Neville Cardus made a similar point in 1955. As more and more Berlioz’s works became widely available on record, professional musicians and critics, and the musical public, were for the first time able to judge for themselves.

A milestone in the reappraisal of Berlioz’s reputation came in 1957, when for the first time a professional opera company staged the original version of The Trojans in a single evening.

It was at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; the work was sung in English with some minor cuts, but its importance was internationally recognized, and led to the world premiere staging of the work uncut and in French, at Covent Garden in 1969, marking the centenary of the composer’s death.

In recent decades Berlioz has been widely regarded as a great composer, prone to lapses like any other.

In 1999 the composer and critic Bayan Northcott wrote that the work of Cairns, Rushton, Sir Colin Davis, and others retained “the embattled conviction of a cause”.

Nevertheless, Northcott was writing about Davis’s “Berlioz Odyssey” of seventeen concerts of Berlioz’s music, featuring all the major works, a prospect unimaginable in earlier decades of the century. Northcott concluded, “Berlioz still seems so immediate, so controversial, so ever-new”.

–

Symphonie fantastique op. 14. Épisode de la vie d’un artiste

In the video, the symphony is performed by the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Alain Altinoglu. The concert took place at the Alte Oper Frankfurt, 10. September 2021.

I. Rêveries – Passions 00:00

II. Un bal 15:30

III. Scène aux champs 21:27

IV. Marche au supplice 37:30

V. Songe d’une nuit du sabbat 45:11

In this video, the symphony is performed by l’Orchestre philharmonique de Radio France conducted by Myung-Whun Chung. The concert took place the 13 septembre 2013 at the Salle Pleyel (Paris).

00:00 – Début du concert

00:35 – 1st movement : Rêveries – Passions (Largo)

15:08 – 2nd movement : Un bal. Valse (Allegro non troppo)

22:09 – 3rd movement : Scène aux champs (Adagio)

39:53 – 4th movement : Marche au supplice (Allegretto non troppo)

44:27 – 5th movement : Songe d’une nuit de sabbat (Larghetto – Allegro)

–

“Grande Messe des Morts” (Requiem für Tenor, gemischten Chor und Orchester op. 5)

In the video, the requiem is performed by Keith Ikaia-Purdy, Chor der Staatsoperette Dresden, Dresden Symphony Chorus, Dresden Singakademie, Staatskapelle Dresden, conducted by Colin Davis. The concert took place at the Royal Albert Hall in London in 2000.

00:00:00 I. Requiem et Kyrie. Andante un poco lento (Chor)

00:08:35 II. Dies irae, Tuba mirum. Moderato – Allegro maestoso (Chor)

00:20:20 III. Quid sum miser. Andante un poco lento (Männerchor)

00:23:18 IV. Rex tremendae. Andante maestoso (Chor)

00:28:48 V. Quaerens me. Andante sostenuto (Chor)

00:33:19 VI. Lacrymosa. Andante non troppo lento (Chor)

00:43:18 VII. Offertorium. Moderato (Chor)

00:51:38 VIII. Hostias. Andante non troppo lento (Männerchor)

00:54:50 IX. Sanctus. Andante un poco sostenuto e maestoso (Tenor, Chor)

01:05:29 X. Agnus Dei. Andante un poco lento (Chor)

Here is another video performance by Andrew Staples, Tenor, Tschechischer Philharmonischer Chor Brno, WDR Rundfunkchor Köln and the WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln conducted by Jukka-Pekka Saraste.

–