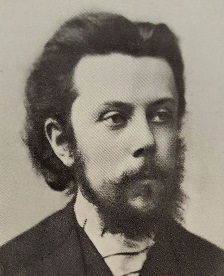

Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (21 March 1839 – 28 1881) was a Russian composer, one of the group known as “The Five”.

He was an innovator of Russian music in the Romantic period. He strove to achieve a uniquely Russian musical identity, often in deliberate defiance of the established conventions of Western music.

Many of his works were inspired by Russian history, Russian folklore, and other national themes.

Such works include the opera Boris Godunov, the orchestral tone poem Night on Bald Mountain and the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition.

For many years, Mussorgsky’s works were mainly known in versions revised or completed by other composers.

For many years, Mussorgsky’s works were mainly known in versions revised or completed by other composers.

Many of his most important compositions have posthumously come into their own in their original forms, and some of the original scores are now also available.

Early years

Mussorgsky was born in Karevo, Toropets Uyezd, Pskov Governorate, 400 km (250 mi) south of Saint Petersburg.

His wealthy and land-owning family, the noble family of Mussorgsky, is reputedly descended from the first Ruthenian ruler, Rurik, through the sovereign princes of Smolensk.

However, his mother Julia Chirikova (1813–1865) was the daughter of a comparatively non-rich nobleman.

Modest’s paternal grandmother Irina used to be a serf that could be sold without land in his grandfather’s estate.

At age six, Mussorgsky began receiving piano lessons from his mother, herself a trained pianist.

At age six, Mussorgsky began receiving piano lessons from his mother, herself a trained pianist.

His progress was sufficiently rapid that three years later he was able to perform a John Field concerto and works by Franz Liszt for family and friends.

At 10, he and his brother were taken to Saint Petersburg to study at the elite German language Petrischule (St. Peter’s School).

While there, Modest studied the piano with the noted Anton Gerke.

In 1852, the 12-year-old Mussorgsky published a piano piece titled “Porte-enseigne Polka” at his father’s expense.

Mussorgsky’s parents planned the move to Saint Petersburg so that both their sons would renew the family tradition of military service.

To this end, Mussorgsky entered the Cadet School of the Guards at age 13.

Sharp controversy had arisen over the educational attitudes at the time of both this institute and its director, a General Sutgof.

All agreed the Cadet School could be a brutal place, especially for new recruits.

More tellingly for Mussorgsky, it was likely where he began his eventual path to alcoholism.

According to a former student, singer, and composer Nikolai Kompaneisky, Sutgof “was proud when a cadet returned from leave drunk with champagne.”

Music remained important to him, however.

Sutgof’s daughter was also a pupil of Gerke, and Mussorgsky was allowed to attend lessons with her.

His skills as a pianist made him much in demand by fellow cadets; for them, he would play dances interspersed with his own improvisations.

In 1856 Mussorgsky – who had developed a strong interest in history and studied German philosophy – graduated from the Cadet School.

Following family tradition, he received a commission with the Preobrazhensky Regiment, the foremost regiment of the Russian Imperial Guard.

Maturity

In 1856, by now a lieutenant, Mussorgsky joined the Preobrazhensky Guards, one of Russia’s most aristocratic regiments, where he made the acquaintance of several music-loving officers who were habitués of the Italian theatre.

During this same period, he came to know Aleksandr Borodin, a fellow officer who was to become another important Russian composer.

Borodin has provided a very vivid picture of the musician:

“There was something absolutely boyish about Mussorgsky; he looked like a real second-lieutenant of the picture books … a touch of foppery, unmistakable but kept well within bounds.

His courtesy and good breeding were exemplary. All the women fell in love with him. … That same evening we were invited to dine with the head surgeon of the hospital. … Mussorgsky sat down to the piano and played … very gently and graciously, with occasional affected movements of the hands, while his listeners murmured, “charming! delicious!”

During the winter of 1856, a regimental comrade introduced Mussorgsky into the home of the Russian composer Aleksandr Dargomyzhsky.

During the winter of 1856, a regimental comrade introduced Mussorgsky into the home of the Russian composer Aleksandr Dargomyzhsky.

At one of the musicales there, Mussorgsky discovered the music of the seminal Russian composer Mikhail Glinka, and this quickened his own Russophile inclinations.

Three years later, in June 1859, he saw the Moscow Kremlin for the first time, an important experience that represented his first “physical” communion with Russian history.

Through Dargomyzhsky, Mussorgsky met another composer, Mily Balakirev, who became his teacher.

Since the death of their father (in 1853), the Mussorgsky brothers had seen their poorly administered patrimony decrease substantially.

With the freeing of the serfs in 1861, it vanished.

Having decided to devote himself to music, Modest Mussorgsky had quit the army three years earlier and since 1863 had been working as a civil servant in the Ministry of Communications.

His distressing financial troubles date from that time, and he had to seek the help of moneylenders.

Mussorgsky achieved artistic maturity in 1866 with a series of remarkable songs about ordinary people such as “Darling Savishna,” “Hopak,” and “The Seminarist,” and an even larger series appeared the following year.

Another work dating from this time is the symphonic poem Night on Bald Mountain (1867).

In 1868 he reached the height of his conceptual powers in composition with the first song of his incomparable cycle Detskaya (The Nursery) and a setting of the first few scenes of Nikolay Gogol’s Zhenitba (The Marriage).

In 1869 he began his great work, Boris Godunov, with his own libretto based on the drama by Aleksandr Pushkin.

The first version, completed in December 1869, was rejected by the advisory committee of the imperial theatres because it lacked a prima donna role.

In response, the composer subjected the opera to a thorough revision and in 1872 put the finishing touches to the second version, adding the roles of Marina and Rangoni as well as several new episodes.

The first production of Boris took place on February 8, 1874, in St. Petersburg and was a success.

In 1865, after the death of his mother, he lived with his brother, then shared a small flat with the Russian composer Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov until 1872, when his colleague married.

Left very much alone, Mussorgsky began to drink to excess, although the composition of the opera Khovanshchina perhaps offered some distraction (left unfinished at his death, this opera was completed by Rimsky-Korsakov).

Mussorgsky then found a companion in the person of a distant relative, Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov.

This impoverished 25-year-old poet inspired Mussorgsky’s two cycles of melancholy melodies, Bez solntsa (Sunless) and Pesni i plyaski smerti (Songs and Dances of Death).

At that time Mussorgsky was haunted by the specter of death—he himself had only seven more years to live.

The death of another friend, the painter Victor Hartmann, inspired Mussorgsky to write the piano suite Kartinki s vystavki (Pictures from an Exhibition; orchestrated in 1922 by the French composer Maurice Ravel).

The last few years of Mussorgsky’s life were dominated by his alcoholism and by a solitude made all the more painful by Golenishchev-Kutuzov’s marriage.

Nonetheless, the composer began his opera Sorochinskaya yarmarka (unfinished; Sorochintsy Fair), inspired by Gogol’s tale.

As the accompanist of an aging singer, Darya Leonova, Mussorgsky departed on a lengthy concert tour of southern Russia and the Crimean Peninsula.

On his return, he tried teaching at a small school of music in St. Petersburg.

On February 24, 1881, three successive attacks of alcoholic epilepsy laid him low.

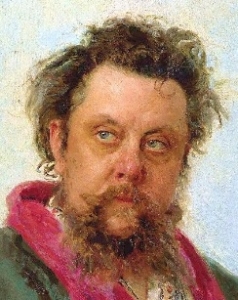

His friends took him to a hospital where for a time his health improved sufficiently for one of the leading Russian artists of the day, Ilya Repin, to paint a famous portrait of him.

Mussorgsky’s health was irreparably damaged, however, and he died within a month, shortly after his 42nd birthday.

Music

Mussorgsky’s importance to and influence on later composers are quite out of proportion to his relatively small output.

Few composers were less derivative or evolved so original and bold a style.

The 65 songs he composed, many in his own texts, describe scenes of Russian life with great vividness and insight and realistically reproduce the inflections of the spoken Russian language.

Mussorgsky’s operas Boris Godunov and to a lesser extent Khovanshchina display his dramatic technique of setting sharply characterized individuals against the background of country and people.

His power of musical portrayal, his strong characterizations, and the importance he assigned to the role of the chorus establish Boris Godunov as a masterpiece.

From a technical standpoint, Mussorgsky’s unorthodox use of tonality and harmony and his method of fusing arioso and recitative provide Boris Godunov with great dramatic intensity.

Shortly after Mussorgsky’s death, Rimsky-Korsakov prepared Mussorgsky’s works for publication, in the process purging them of what he considered to be their harmonic eccentricities and instrumental weaknesses.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s widely performed edition of Boris Godunov is the best known of these works.

From roughly 1908, however, after the production of Rimsky-Korsakov’s version of Boris Godunov at the Paris Opera, there was a growing demand for the original versions of Mussorgsky’s works, which were made available beginning in 1928 in a collected edition edited by Paul Lamm.

This edition displayed Mussorgsky’s original orchestration for Boris Godunov, which is as stark and economical as his unorthodox harmony.

–

Pictures at an Exhibition

The suite is Mussorgsky’s most famous piano composition and has become a showpiece for virtuoso pianists. It has become further known through various orchestrations and arrangements produced by other musicians and composers, with Maurice Ravel’s 1922 version for full symphony orchestra being by far the most recorded and performed.

Orchestral version

In the video, Maurice Ravel‘s version for full symphony orchestra is performed live by the Karol Szymanowski Youth Symphony Orchestra in Katowice, Poland conducted by Maciej Tomasiewicz. The concert took place on 28th September 2019 in Teatr Wielki – Polish National Opera.

0:00 Applause

0:25 Promenade

1:55 The Gnome

4:28 Promenade

5:29 The Old Castle

10:22 Promenade

10:49 Tuileries (Children’s Quarrel after Game)

11:55 Cattle

14:43 Promenade

15:30 Ballet of Unhatched Chicks

16:50 Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle

18:59 Limoges. The Market (The Great News)

20:32 Catacombs (Roman Tomb)

22:00 With the Dead in a Dead Language

23:52 The Hut on Hen’s Leg (Baba Yaga)

27:21 The Great Gate of Kiev

Piano version

In this video, the original piano version (A Remembrance of Viktor Hartmann) is performed by pianist Yulianna Avdeeva.

0:00 – Promenade

1:16 – Gnomus

3:50 – Promenade

4:40 – Il Vecchio Castello

8:49 – Promenade

9:12 – Les Tuileries

10:14 – Bydlo

13:41 – Promenade

14:23 – Dance of Chickens in their Shells

15:29 – Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle

17:49 – Promenade

19:03 – The Market at Limoges

20:28 – Catacombe

22:23 – Cum Mortuis in Lingua Mortua

24:15 – Baba-Yaga

27:34 – The Great Gate of Kiev

In this video, the piano version is performed by Yulianna Avdeeva at a live concert at St. Petersburg Academic Philharmonia. As an encore Tchaikovsky’s Meditation op. 72/5 is performed.

0:49 Promenade

2:08 Gnomus

4:42 Promenade

5:31 Il Vecchio Castello

9:40 Promenade

10:04 Les Tuileries

11:05 Bydlo

14:30 Promenade

15:08 Dance of Chickens in their Shells

16:21 Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle

18:41 Promenade

19:55 The Market at Limoges

21:19 Catacombe

23:14 Cum Mortuis in Lingua Mortua

25:06 Baba-Yaga

28:26 The Great Gate of Kiev

35:49 Tchaikovsky: Meditation op. 72/5 (Encore)

Night on Bald Mountain

This describes a short story in which St John sees a witches’ Sabbath on the Bald Mountain near Kyiv in the old Russian Empire.

It’s a wild and terrifying party with lots of dancing but when the church bell chimes at 6 am and the sun comes up the witches vanish.

Mussorgsky wrote a number of different versions of this piece of music. When he was finally satisfied with it, his music teacher told him it wasn’t good enough so he put it aside for years.

Eventually, his friend and fellow composer Rimsky-Korsakov re-arranged the music for orchestra and this is the piece we know today.

This video presents a performance by Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Yuri Botnari.

Pieces from Khovanshchina

Khovanshchina is an opera (subtitled as a ‘national music drama’) in five acts by Modest Mussorgsky. The work was written between 1872 and 1880 in St. Petersburg, Russia. The composer wrote the libretto based on historical sources. The opera was unfinished and unperformed when the composer died in 1881.

Like Mussorgsky’s earlier Boris Godunov, Khovanshchina deals with an episode in Russian history, first brought to the composer’s attention by his friend Vladimir Stasov.

It concerns the rebellion of Prince Ivan Khovansky, the Old Believers, and the Streltsy against Peter the Great, who was attempting to institute Westernizing reforms in Russia.

Peter succeeded, the rebellion was crushed, and (in the opera, at least) the Old Believers committed mass suicide.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov completed, revised, and scored Khovanshchina in 1881–1882.

Because of his extensive cuts and “recomposition”, Dmitri Shostakovich revised the opera in 1959 based on Mussorgsky’s vocal score, and it is the Shostakovich version that is usually performed.

In 1913 Igor Stravinsky and Maurice Ravel made their own arrangement at Sergei Diaghilev’s request.

The Stravinsky-Ravel orchestration was forgotten, except for Stravinsky’s finale, which is still used.

Although the setting of the opera is the Moscow Uprising of 1682, its main themes are the struggle between progressive and reactionary political factions during the minority of Tsar Peter the Great and the passing of old Muscovy before Peter’s westernizing reforms.

It received its first performance in the Rimsky-Korsakov edition in 1886.

The video presents the Prelude to Khovanshchina (Dawn on the Moskva River) performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Georg Solti.

This video presents Dance of the Persian Slaves (from act IV) performed by the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra conducted by Valery Gergiev. Alexandra Iosifidi is the solo ballet dancer.

–

Pieces for piano

In the video, the following pieces are performed by pianist Alexander Bakhchiev.

1. Memories of childhood. Kids Games (00:00)

2. Passionate impromptu (02:40)

3. In the village (06:29)

4. On the southern coast of Crimea (10:31)

5. Seamstress (15:11)

6. Minx (17:22)

7. Near the southern coast of Crimea. Kayaks (20:34)

8. Polka (24:12)

9. Thought (26:29)

10. Memories of childhood. Nanny and I (30:56)

11. Thinking (32:32)

12. Memories of childhood. The first sentence. (37:31)

13. Tear (38:51)

–