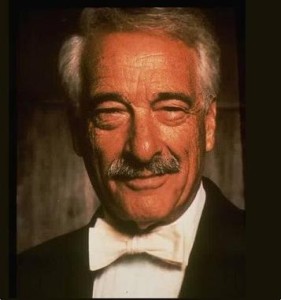

Victor Borge

The Great Musical Humorist of Denmark

Victor Borge was a Danish humorist, conductor, and pianist who achieved great popularity on radio and television in the United States and Europe. His blend of music and comedy earned him the nicknames ”The Comedian of the Keyboard”, “The Clown Prince of Denmark”, “The Unmelancholy Dane”, and “The Great Dane”.

Mr. Borge made Broadway history in the 1950s when his show, ”Comedy in Music,” ran for 849 performances at the Golden Theater, a record for a one-man engagement. He still holds this world record. He went on to perform ”Comedy in Music” around the globe, bringing revised editions of it back to Broadway.

With ”Comedy in Music,” Mr. Borge perfected a blend of comedy and virtuosic pianism that combined musical satire with sight gags and verbal quips.

On this page, you will find his biography, an interview, some quotes, and videos of Victor Borge’s best performances including “page-turner”, “hands-off”, “phonetic punctuation”, “Mozart opera” and many others.

Childhood in Copenhagen

Childhood in Copenhagen

Victor Borges original name was Børge Rosenbaum. He lived from 3 January 1909 to 23 December 2000. He was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, into a Jewish family.

He was the youngest of the five sons of Bernhard Rosenbaum, a violinist with the Royal Danish Symphony.

Introduced to the piano by his mother, the former Frederikke Lichtinger, at the age of 3, he made his concert debut in Copenhagen when he was 8.

Hailed as a prodigy, he was given a scholarship to the Copenhagen Music Conservatory, and while still in his teens, he studied in Vienna under Victor Schiøler, the leading Danish pianist.

He also studied in Berlin with Frederic Lamond, a pupil of Liszt’s, who was the most celebrated Beethoven pianist of his time.

”He even looked like Beethoven,” Mr. Borge told Harold C. Schonberg, the chief music critic of The New York Times, in 1989. ”I did not like him. He was harsh and domineering. Besides, I did not think he played very well. Also, he was a Beethoven pianist and I am not. I’m much more a Romantic. Lamond played with curved fingers, like claws. He told me I should be a conductor. Back to Denmark, I went.”

Later he returned to Berlin to study with Egon Petri. ”That was wonderful,” Mr. Borge remembered. ”Petri was such a sweet man. He gave me a quality of finesse I never had. Petri must have seen something in me, raw as I was. I was on my way toward becoming a first-class concert pianist.”

Later he returned to Berlin to study with Egon Petri. ”That was wonderful,” Mr. Borge remembered. ”Petri was such a sweet man. He gave me a quality of finesse I never had. Petri must have seen something in me, raw as I was. I was on my way toward becoming a first-class concert pianist.”

Borge played his first major concert in 1926 at the Danish concert hall Odd Fellow Palæet (The Odd Fellow’s Lodge building).

But he was not destined to be a concert pianist. Mr. Borge told Mr. Schonberg that he never had the sitzfleish — ”the application of the seat of the pants to the seat of the chair” — that a great pianist must have.

Instead, he exploited his growing reputation as a parlor comedian and began to do nightclub turns, becoming a headliner at the Gypsy Hall in Copenhagen.

He started his now-famous “stand up” act, with the signature blend of piano music and jokes.

He also started to do some acting and appeared in a few films as a comic. In 1933 he married an American, Elsie Chilton.

Over the next few years, Mr. Borge became known in Scandinavia as a comic actor, composer, pianist, writer, and director of movies, stage shows, and radio programs.

But his rise as a performer coincided with the rise of fascism and as a Jew in Denmark, he was threatened by the local Nazi bund. He reacted with a combination of anger and fear and he almost left the stage.

But instead, he worked up a series of anti-Nazi sketches. When Denmark and Germany signed a non-aggression pact, he joked, ”How nice. Now the Germans can sleep in peace, knowing that they will not be invaded by us.”

Another of his observations went: ”What is the difference between a Nazi and a dog? A Nazi lifts his arm.”

Fleeing the nazis

He was performing in Sweden at the time of the German invasion of Denmark and escaped to the United States in 1940 from Finland.

”I went to the American Consulate in Stockholm, and one of the officers there turned out to be a fan of mine,” he recalled. ”I got a visa to Finland.”

From there he sailed to the United States. ”I got to the ship just as they were pulling up the gangplank,” he said. ”It was the last boat to leave Finland for a long time.”

Later in his life, he became a founder of the Thanks to Scandinavia Foundation, which offers scholarships to Scandinavian students in recognition of the role of their countrymen in saving Jews during World War 11.

He arrived in New York on 28 August 1940, with only $20 (about $337 today), with $3 going to the customs fee. Disguised as a sailor, Borge returned to Denmark once during the occupation to visit his dying mother.

—

In the video below (Act 1 and Act 2 together) Victor Borge performs live on stage “the page-turner”, “hands-off”, “inflationary language”, “two pianists playing Liszt’s 2nd Hungarian Rhapsody on one piano”, “Mozart opera” and “phonetic punctuation” as an encore.

—

In the U.S.A.

Even though Borge did not speak a word of English upon arrival, he quickly managed to adapt his jokes to the American audience, learning English by watching movies.

For 15 cents he could watch the film three times and, by the third showing, he would try to repeat every word.

He took the name of Victor Borge, and, in 1941, he started on Rudy Vallee’s radio show, but was hired soon after by Bing Crosby for his Kraft Music Hall program performing to 30 million Americans every week.

From then on, fame rose quickly for Borge, who won Best New Radio Performer of the Year in 1942. Soon after the award, he was offered film roles with stars such as Frank Sinatra (in Higher and Higher).

While hosting The Victor Borge Show on NBC beginning in 1946, he developed many of his trademarks, including repeatedly announcing his intent to play a piece but getting “distracted” by something or other, making comments about the audience, or discussing the usefulness of Chopin’s “Minute Waltz” as an egg timer.

He would also start out with some well-known classical piece like Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” and suddenly move into a harmonically suitable pop or jazz tune like Cole Porter’s “Night and Day” or “Happy Birthday to You”.

One-man Show: Comedy in Music

Borge appeared on Toast of the Town hosted by Ed Sullivan several times during 1948.

He became a naturalized citizen of the United States the same year. He started the Comedy in Music show at John Golden Theatre in New York City on 2 October 1953.

Comedy in Music became the longest-running one-man show in the history of theater with 849 performances when it closed on 21 January 1956, a feat which placed it in the Guinness Book of World Records.

One of the trademarks of an act that took years to develop was ”phonetic punctuation,” in which Mr. Borge substituted amusing nonsense sounds for periods, commas and exclamation points.

In another routine, he would seat himself at the piano and after elaborate preparation and many false starts never get around to playing the instrument.

Typical of the musical jokes that displayed his keyboard skill was his interpolation of ”Happy Birthday” into the music of Chopin, Beethoven, Mozart, and Debussy.

There also would be stories about his father, or his grandfather, who invented a soft drink called 3-Up, then improved it to 4-Up and 5-Up, marketed it as 6-Up and died broken-hearted when it was not a success.

When he accompanied Frank Sinatra singing ”Autumn Leaves” at Radio City Music Hall, leaves started drifting down, then began falling thicker and faster until Mr. Borge cowed underneath his piano.

He was fond of stumbling into a Steinway, sounding a chord with his backside, and then confessing to his audience, ”I play much better by ear, I can assure you.”

He developed a routine involving ”inflated language,” in which ”wonderful” became ”twoderful” and ”create” became ”crenine.”

Over the years his writers included Alan Jay Lerner, Henry Morgan, Mel Brooks and Neil Simon, but Mr. Borge always preferred to write his own material.

Many of his best lines began as ad-libs that he then worked into his act.

Although some of his routines would not change in half a century, with each change of audience or venue, he remained alert to the possibilities of improvisation.

Once, after a large fly landed on his nose during a performance, he effortlessly cracked so many jokes about it that people afterward asked him how he had managed to train the fly to be part of his act.

Arriving in the United States virtually penniless and unable to speak English, the pianist eventually taught himself the language by spending hundreds of hours in movie houses.

He changed his name to Victor Borge and after translating some of his comedy routines into English, began performing in nightclubs.

In California, he got a job warming up audiences for Rudy Vallee’s popular radio show.

After a successful guest appearance on Bing Crosby’s ”Kraft Music Hall” radio series in December 1941, Mr. Borge became a regular member of the cast, and by the time he left the program in 1943, he had developed a national following. In the summer of 1945 he had his own radio show on NBC.

That fall he also made his American concert debut at Carnegie Hall, where he interspersed some of his comedy routines with serious piano playing and conducted a 45-piece orchestra.

His career soared with increased appearances on concert stages and in nightclubs and later on the most popular television variety programs of the day, especially ”The Ed Sullivan Show.”

Against the advice of many friends, Mr. Borge opened ”Comedy in Music” on Broadway on Oct. 2, 1953. Originally booked for two weeks, it won favorable reviews and ended up running for nearly three years and grossing more than $2 million. From Broadway,

Mr. Borge took the show on a five-month tour and returned in triumph to Europe, where he entertained thousands of United States troops.

When Mr. Borge brought the show back to Broadway for a limited engagement in 1964, he was assisted by the concert pianist Leonid Hambro.

For the show’s second return engagement on Broadway in 1977, he was joined by the young opera singer Marylyn Mulvey.

At the piano Mr. Borge remained facile and elegant, and he produced s a sound that reflected a school of piano playing that is all but extinct.

Mr. Schonberg of The Times described it as ”a warm, rich, highly nuanced sound” that Mr. Borge achieved ”through pedal mixtures and by the formation of his own hands — large, spatulate hands with cushions on each fingertip.”

During the later years of his career, Mr. Borge flourished as a conductor of classical music.

The many orchestras he conducted included the London Philharmonic, the Concertgebouw of Amsterdam, the Royal Copenhagen and the major orchestras in New York, Philadelphia and Cleveland.

He and his wife divorced — they had two young children — and in 1953 Mr. Borge married Sanna Roach, who had become his manager.

Sanna Borge died in September. Mr. Borge is survived by two sons, Ronald Borge of Rowayton, Conn., and Victor Bernhard Borge of Manhattan; three daughters, Sanna Feirstein of Manhattan, Janet Crowle of St. Michaels, Md., and Frederikke Borge of South Egremont, Mass.; nine grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Mr. Borge lived for many years on a 10-bedroom, 4.5-acre waterfront estate in Greenwich, Conn., where he kept two concert grands — a Steinway and a Bosendorfer — back to back. ”When I do four hands, I run around,” he told a visitor. ”Or, with two hands, I play it twice.”

Through the 1970’s and 80’s, Mr. Borge continued to tour internationally, performing about 150 shows a year.

In 1984 he celebrated his 75th birthday with a tour that culminated in a series of 12 Carnegie Hall performances.

When he was 90, he was still performing about 60 shows a year and reaching even more people through videotapes and CD’s.

He was showered with awards. He was knighted by all the Scandinavian countries and honored by the United States Congress and the United Nations.

President Clinton hailed him in 1999, when he was honored by the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington. Queen Elizabeth told him, ”I grew up on your records.”

For many years he raised and marketed Red Cornish game hens. He also bought an 18th-century house in St. Croix. A boating enthusiast, he enjoyed sailing with his family between his two homes.

Mr. Borge recalled that when he was about 12 he saw a Russian pianist in Copenhagen accidentally fall off the piano bench. ”Such a cheap slapstick thing,” he said, but he began doing it himself intentionally for decades as part of his act.

When he approached 90, his doctors warned him against it. So, he told Ralph Blumenthal of The Times in 1999, ”I still don’t do it.” But of course, he did, in every show.

Mr. Schonberg asked Mr. Borge why he continued to maintain a crushing schedule.

”Why not?” Mr. Borge said. ”If it was a strain, I wouldn’t do it. But I can do it. I haven’t faltered yet. I know life. I have had a full measure of experience. Shouldn’t I take advantage of it? These days my acts are the essence of what I have accomplished. The fruit is on the tree. Should I let it rot?

”What I do, I do well and I know it. I have always worked for two audiences at the same time. One is sophisticated, the other not musically oriented.

I notice that the ones who laugh most are composed of professionals, as when I do my act with orchestras. But my jokes must be understood by everybody. Nobody must be bored. It is a fine line that I walk.”

Continuing his success with tours and shows, Borge played with and conducted orchestras including the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic and London Philharmonic.

Always modest, he felt honored when he was invited to conduct the Royal Danish Orchestra at the Royal Danish Theatre in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1992.

Victor Borge continued to tour until his last days, performing up to 60 times per year when he was 90 years old.

Borge helped start several trust funds, including the Thanks to Scandinavia Fund, which was started in dedication to those who helped the Jews escape the German persecution during the war.

Author of three books

Aside from his musical work, Borge wrote three books, ‘My Favorite Intermissions’ and’ My Favorite Comedies in Music’ (both with Robert Sherman), and the autobiography (in Danish) ‘Smilet er den korteste afstand’ (The Smile is the Shortest Distance) with Niels-Jørgen Kaiser.

Borge died in Greenwich, Connecticut, at the age of 91, after more than 75 years of entertaining.

He died peacefully in his sleep a day after returning from a concert in Denmark.

According to his wish, to mark his connection to both the United States and Denmark, a part of Victor Borge’s ashes is interred at Putnam Cemetery in Greenwich, with a replica of Danish icon The Little Mermaid sitting on a large rock at the gravesite, the other part in Western Jewish Cemetery, Copenhagen, Denmark.

References:

Victor Borge in Wikipedia

Obituary in the New York Times

Obituary in the Telegraph

Victor Borge: My Favorite Intermissions

Victor Borge: My Favorite Comedies in Music

Victor Borge Quotes:

–

The Smile is the Shortest Distance

–

A Smile is a curve that can set a lot of things straight

–

Humor is something that thrives between man’s aspirations and his limitations. There is more logic in humor than in anything else. Because you see, humor is truth

–

Always remember to forget the things that made you sad, but never forget to remember the things that made you glad

–

I wish to thank my parents for making it all possible… and I wish to thank my children for making it necessary

–

Borge: “Are there any children in the audience?”

Audience: “Yes.”

Borge: “Out!” —— Addressing the manager: “We do have some children in here; that means I can’t do the second half in the nude. —– I’ll have to wear a tie. —— The long one. —– The very long one, yes.”

Phonetic Punctuation

Reciting a story, with full punctuation (comma, period, exclamation mark, etc.) as exaggerated onomatopoeic sounds.

Inflationary Language

Incrementing numbers embedded in words, whether they are visible or not (“once upon a time” becomes “twice upon a time”, “wonderful” becomes “twoderful”, “forehead” becomes “fivehead”, “tennis” becomes “elevennis”,

“I ate a tenderloin with my fork and so on and so forth” becomes “‘I nine an elevenderloin with my five’k’ and so on and so fifth”.

–